At the peak of his literary fame, James Baldwin yearned for seclusion. He found it in Istanbul, where he lived on and off between 1961 and 1971. Baldwin was suffering from writer’s block when he arrived in the Bosporus-divided city thirteen years after settling in Paris. Soon after, he completed Another Country, a manuscript that had long been haunting him. In Istanbul, the author found the time and inspiration for some of his career-defining works, and he later wrote about the city in an unfinished novel. He also made friends, among them Sedat Pakay, a young engineering student and amateur photographer who was twenty years his junior. The pair met through a mutual friend at a party in 1964. The younger man, then a member of his university’s photography club, offered to shadow Baldwin with his camera. Baldwin accepted. Over the next several years, Pakay accompanied Baldwin as he wandered across Istanbul, producing a series of photographs as well as an eleven-minute-long film, James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973), that document Baldwin’s time in the city.

Pakay’s photographs of Baldwin are currently on view in Turkey Saved My Life: Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961–1971, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Public Library. The show was organized by Atesh M. Gundogdu, the publishing director of the website Artspeak NYC, along with the library’s Cora Fisher and Lászlo Jakab Orsós, and it occurs in the middle of what would have been Baldwin’s one hundredth year. (He died in 1987, at the age of sixty-three.) The pictures displayed narrate Baldwin’s unlikely bond with a young man from Turkey who had a discerning lens.

From 1966 to 1968, Pakay lived in the United States, where he had enrolled in an M.F.A. program in photography at the Yale School of Art. During this time, he kept up a correspondence with Baldwin. Today, Pakay’s letters are in the collection of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The archive is a donation from Pakay’s widow, Kathy, and their son Timur.

Below are six photographs from Turkey Saved My Life, which runs through March 15, 2025.

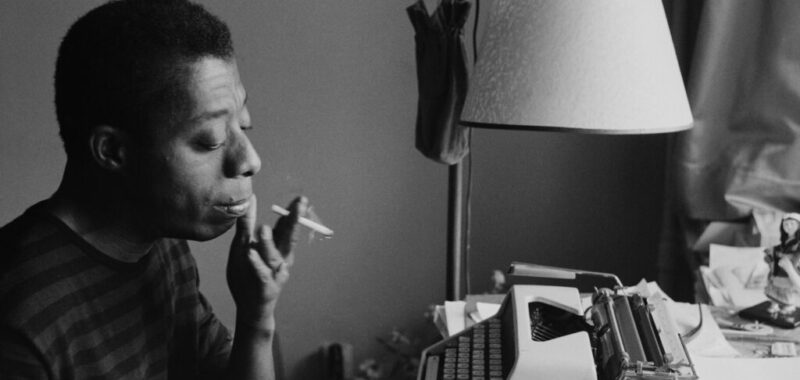

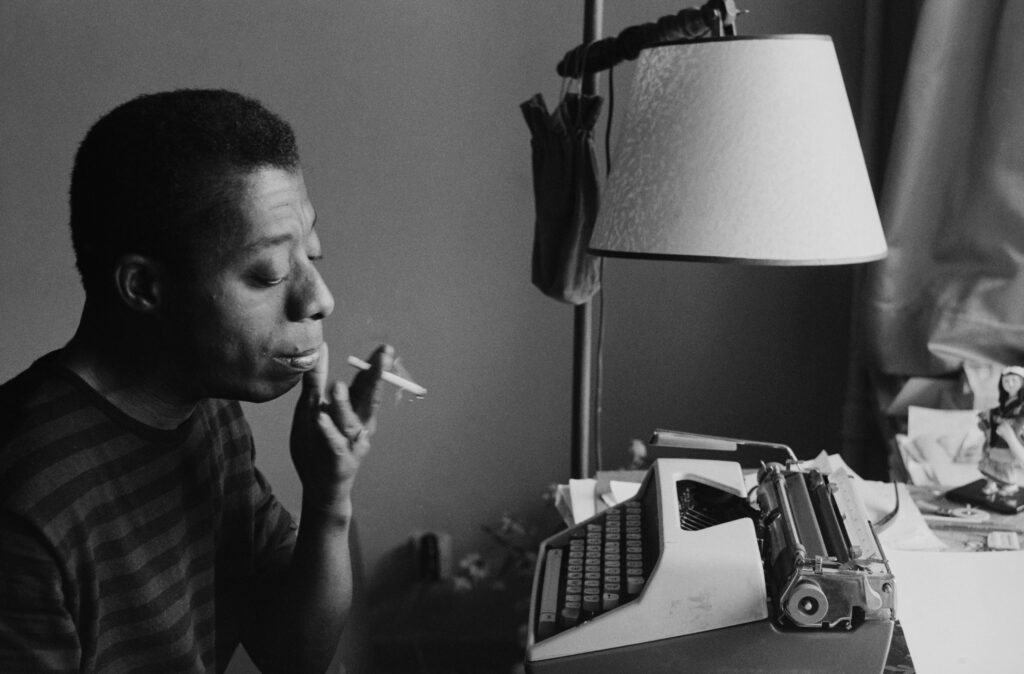

Baldwin working on his novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, 1965.

Baldwin’s decision to visit Istanbul for the first time in 1961 was heavily influenced by Engin Cezzar, a Turkish actor who had appeared in a 1958 production of Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room at the Actors Studio in New York. Cezzar would go on to star in a Turkish adaptation of the John Herbert play Fortune and Men’s Eyes, which Baldwin directed in Istanbul in 1969, despite not speaking Turkish. It was Cezzar who connected Baldwin with the writers and actors—including Cezzar’s wife, the Turkish actor, author, and cooking-show host Gülriz Sururi—who would become his community in Istanbul. In fact, Cezzar and Sururi hosted the party at which Baldwin met Pakay, who had been invited by his professor, the painter Özer Kabaş. The photo above shows Baldwin working on his fourth novel, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, at his apartment in Istanbul’s Taksim neighborhood.

A sherbet seller, his customers, and Baldwin at Yeni Cami (New Mosque), 1965.

“James loved to speak in exaggerated terms, but it is in a way true that Turkey saved his life,” David Leeming told me over the phone. Leeming was Baldwin’s long-term assistant and is the author of 1994’s James Baldwin: A Biography. The two also met at a party in Istanbul, in 1962, when Baldwin was finalizing his draft for Another Country, the other seminal work that he produced during his years in the city. “There was too much expectation of him in the U.S., and even in his second home, Paris, where he was also well known by the early sixties,” Leeming added. “He was isolated and could lead a normal routine in Istanbul without understanding Turkish or being stopped on the streets.” Here he is shown sitting outside the Yeni Cami, also known as the New Mosque, to the right of a sherbet seller and his customers.

Baldwin and sailors from the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet near the Blue Mosque, 1965.

While Baldwin often enjoyed roaming the streets incognito, at other times he embraced his celebrity. In this photograph he is shown with a group of U.S. Navy sailors from the Sixth Fleet, which had docked nearby. They had recognized Baldwin near the Blue Mosque. “One of the marines had in his pocket a Baldwin book with his face on the back, and he asked for an autograph,” Kathy Pakay remembers.

Baldwin and Bertice Reading at Baldwin’s summer house in Kilyos, on the Black Sea, 1965.

Baldwin was extremely social. “James couldn’t say no to anyone—he would get four invitations a night and he would make sure to make each visit,” recalls Kathy Pakay. He also occasionally hosted friends from the United States at his summer rental house in the beach town of Kilyos, an hour’s drive from the city. Among his guests were Marlon Brando, whom Baldwin had invited for a visit when the two met for dinner in London. Here Baldwin is shown with the jazz singer Bertice Reading, who visited Kilyos in 1965.

Baldwin being rowed along the Golden Horn, 1965.

Baldwin never saw the opening of the Bosporus Bridge, which has connected the European and Anatolian sides of Istanbul since 1973. Like many locals, Baldwin zigzagged between the two continents by boat, rowed through the choppy waters by old fishermen and accompanied by seagulls. “James wasn’t much of a sightseer, but he enjoyed the boat rides,” says Leeming.

Baldwin on the Galata Bridge, 1965.

Kathy Pakay remembers this image of Baldwin on the Galata Bridge, with the Golden Horn behind him, as her husband’s favorite of his picture repertoire. When Pakay enrolled in the photography program at Yale, where he studied with Walker Evans, Baldwin sponsored his visa. Although Pakay and Baldwin began to lose touch in the late seventies, they would reunite occasionally. In 1969, following Pakay’s graduation from Yale, the two met again in Los Angeles, where Baldwin was at work on a screenplay adaptation of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Osman Can Yerebakan is a New York–based art, culture, and design writer.