SAN JACINTO, Calif. — A paradox has settled across California’s velvet green fields and orchards. California farmers, who are some of the most ardent supporters of Donald Trump, would seem to be on a collision course with one of the president-elect’s most important campaign promises.

Trump has promised to carry out mass deportations of undocumented immigrants across the country, including, he has said in recent days, rounding up people and putting them in newly built detention camps.

If any such effort penetrated California’s heartland — where half the fruits and vegetables consumed in the U.S. are grown — it almost surely would decimate the workforce that farmers rely on to plant and harvest their crops. At least half of the state’s 162,000 farmworkers are undocumented, according to estimates from the federal Department of Labor and research conducted by UC Merced. Without sufficient workers, food would rot in the fields, sending grocery prices skyrocketing.

If the Trump administration conducts mass deportation efforts in California’s heartland, farm contractors and other experts said it would decimate the workforce

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

And yet, farmers are not railing in protest. Many say they expect the president will support their workforce needs, either through a robust legalization program for workers already here or by leaving farms be and focusing enforcement elsewhere.

Some are also pushing the government to make it easier for them to import temporary guest workers under the H-2A visa program, which allows farms to hire seasonal agricultural workers when the domestic labor supply falls short.

Karoline Leavitt, a spokesperson for the Trump-Vance transition team, did not respond to questions about agricultural workers specifically, but said: “The American people reelected President Trump by a resounding margin, giving him a mandate to implement the promises he made on the campaign trail, like deporting migrant criminals and restoring our economic greatness. He will deliver.”

In that context, Steve Scaroni, the founder one of the largest guest-worker companies in the country, Fresh Harvest, predicted an increased demand for the thousands of workers his company brings in each year from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador for three- to 10-month stints picking lettuce, strawberries and other crops.

“Most farmers are realizing that they’re going to need to implement the H-2A program at some level to assure that they have labor,” Scaroni said. “Because we just don’t know what the deportation is going to look like.”

Farmworkers and their advocates are anxious — both at the prospect of mass deportations and a huge expansion of guest worker programs that in the past have spawned complaints about shorted paychecks, unpaid travel time and unsafe housing.

Sara, a farmworker living in Riverside County who asked to be identified by only her first name because she is undocumented, said she and fellow workers harvesting cilantro in the eastern Coachella Valley share a pervasive sense of dread.

“Undocumented people are the ones who are really doing the tough work,” she said, “because we need to make money to feed our children and elderly.”

Asked about calls to expand the H-2A program, Sara responded: “Why not give work permits to the people who are already here, instead of bringing more people, when there are lots of farmworkers here already?”

Whatever happens, said Edward Orozco Flores, faculty director of UC Merced’s Community and Labor Center, people should be braced for disruption.

“Up to this point, it was just campaign rhetoric,” he said. “Now comes the messy part.”

For decades, California farmers and the workers who tend their crops have been engaged in a complicated ballet. It is technically illegal for farmers to hire undocumented workers, but some people in the industry say it happens regularly, an assertion research backs up.

One major hiring route is through farm labor contractors, who seek out workers, request their government paperwork and dispatch the workers to farms during harvest and planting seasons. The contractors routinely tell farmers that the workers have valid paperwork. But, according to people knowledgeable about the industry, they don’t always verify that paperwork.

“Our hard stance is we are not document experts,” said one farm labor contractor, who asked not to be identified to discuss sensitive legal matters. He noted that workers give him Social Security numbers. And months later, he said, he often receives notice from the government informing him that many of those numbers do not match the names the workers have given. But by then, the harvest is over and the workers are gone.

“Everybody knows how the game is played,” he said.

Given this state of affairs, he predicted: “If any of these mass deportations happen, it’s going to be catastrophic” for the industry.

It’s not yet clear how Trump’s rhetoric on deportations will play out. He and his advisers have stressed that their first priority will be criminals and those who pose a threat to national security. It is possible that most farmworkers, documented or not, would be unaffected.

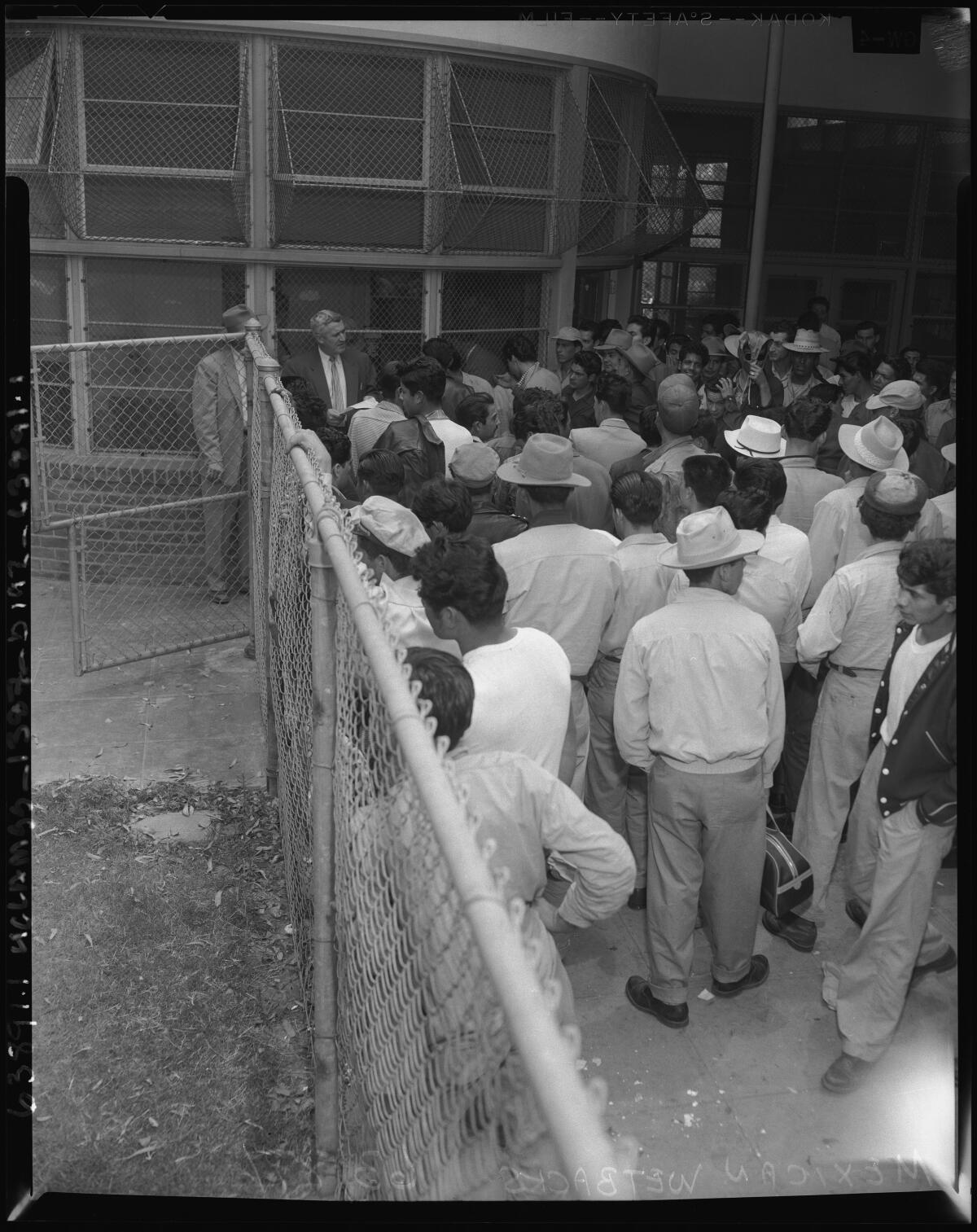

One potential model for what could come next is a deportation campaign the U.S. launched 75 years ago, under President Eisenhower. Trump has spoken admirably of it in the past, telling “60 Minutes” in 2015: “You look back in the 1950s, you look back at the Eisenhower administration, take a look at what they did, and it worked.”

The government called it “Operation Wetback,” and in June 1954, authorities dispatched officers across the Southwest. In the first days of the campaign, border patrol agents set up roadblocks from California to Texas, arresting thousands of people of Mexican descent and sending them south on buses, trains and airplanes. Among those removed were not just undocumented workers, but also American citizens caught up in a racist dragnet.

A 1954 photograph of Mexican workers awaiting deportation during “Operation Wetback.”

(Los Angeles Times / UCLA Archives)

As the campaign continued, officers swept north into cities. They raided landmarks such as the Biltmore and Beverly Hills hotels, and a detention camp was set up in Los Angeles’ Elysian Park to temporarily house the people picked up. Officers also swarmed the fields, scooping up workers near Salinas, Fresno and Sacramento.

Dolores Huerta, now 94 and one of the founders of the United Farm Workers, was then a young woman in Stockton. She vividly recalled agents raiding the hotel her mother owned and a movie theater across the street. Huerta said the fear created by those raids helped propel her into the fight for farmworker rights.

Then, as now, many of the people who toiled in agricultural fields were from Mexico. The deportation program did not change that, but it did alter the terms under which many workers labored.

Sandra Reyes, right, with the legal services group TODEC, is hosting “Know Your Rights” event for farmworkers who might be affected by deportation efforts.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Following the deportation sweeps of 1954, according to UCLA history professor Kelly Hernandez, border patrol officers pressed farmers, particularly in south Texas, to stop hiring undocumented workers and instead avail themselves of the bracero program. That guest worker program was launched during World War II to bring Mexican workers to America’s fields while American workers were fighting overseas, and continued to grow after the war ended. According to statistics from the University of Colorado, the number of braceros in the United States jumped by more than 100% from 1952 to 1956, rising to 445,000.

Many braceros ultimately settled in the U.S. But while in the program, many were subject to exploitation, working long hours for little money and facing demeaning treatment at work sites.

Antonio De Loera-Brust, a spokesperson for the UFW, said he fears similar abuses could follow an expansion of the H-2A program.

Under H-2A, agricultural employers can hire workers from other countries on temporary permits, so long as they show they were unable to hire U.S. workers first. The imported worker is dependent upon the employer for food, housing and safe working conditions.

De Loera-Brust called the program “a recipe for exploitation” because a worker’s permission to be in the country is tied to the employer. “Employers control nearly every aspect of the workers’ lives,” he said.

NumbersUSA, which bills itself as the nation’s largest grassroots immigration-reduction organization, supports use of the H-2A program in agriculture. However, the organization doesn’t support expanding the program to include full-time jobs or jobs not directly tied to farm work, noting there are many unemployed U.S.-born adults.

“It is not plausible for the agribusiness lobby to argue that employers in this sector cannot recruit, train, and retain workers from this large labor pool,” said Eric Ruark, research director for NumbersUSA.

Manuel Cunha Jr., president of the Fresno-based Nisei Farmers League, said he plans to work urgently on legislation that would provide work authorization for current farmworkers and ensure that longtime workers benefit from the Social Security system that they and their employers have paid into.

Cunha also aims to revise the wage structure in the H-2A program. In California, employers must pay H-2A workers $19.75 per hour — the second highest rate in the country, after Washington, D.C. — unless the prevailing hourly rate, the collective bargaining rate, or the applicable state or local minimum wage is higher.

The wages are designed to ensure that the hiring of foreign guest workers doesn’t adversely affect the working conditions of U.S. workers. But at that rate, Cunha said, California “can’t compete” with producers in states such as Florida, where the required wage for H-2A workers is $14.77 an hour, unless other wages are higher.

Fresno County farmer Joe Del Bosque recalls earlier crackdowns on illegal immigration that left unpicked crops rotting in the fields.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Fresno County farmer Joe Del Bosque says it’s still unclear what the Trump administration has planned for undocumented farmworkers. But he said he has concerns.

Del Bosque knows federal policies can have real impacts in the fields. The last time he experienced a serious labor shortage, he said, was under the Obama administration. During that period, fewer people were entering the country due to tight border security, more people were being targeted for deportation, and others weren’t working out of fear, he said.

“During Obama, there were times where I didn’t have enough people show up, and we couldn’t get the crops picked and we left some of the crops to rot in the fields,” he said. “That hurt me, and I’m sure it hurt the people who probably wanted to be working here, but they couldn’t come.”

In the past, Del Bosque has been active in advocating for immigration reform, including the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, which would have revised the H-2A visa program and created a certified agricultural worker status, to provide eligible laborers with employment authorization and an optional path to residency.

This time around, Del Bosque wants to send a message directly to Trump.

“A country can’t be strong if it doesn’t have a reliable food supply,” Del Bosque said, “and we can’t do that without a reliable workforce.”

This article is part of The Times’ equity reporting initiative, funded by the James Irvine Foundation, exploring the challenges facing low-income workers and the efforts being made to address California’s economic divide.