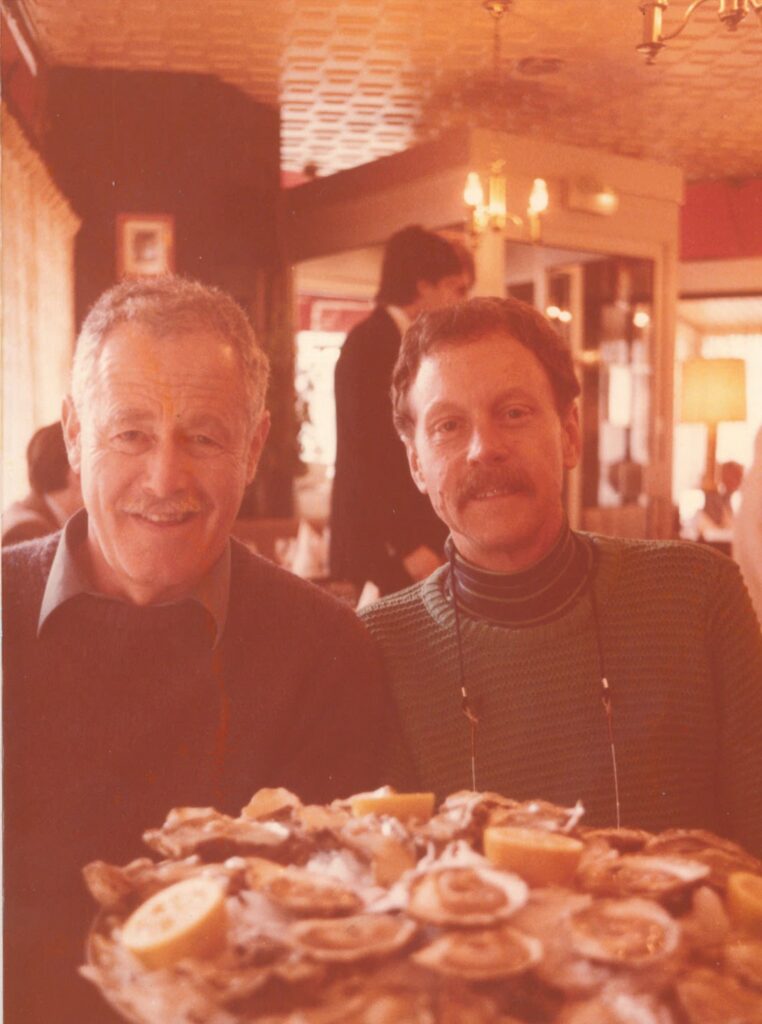

James Salter, at left, and William Benton in Paris, 1985. Photograph courtesy of Kay Eldredge.

Life passes into pages if it passes into anything.

—James Salter

I glanced up from my desk as an attractive couple came into the gallery. We exchanged greetings. They made a cursory tour of the space. I’d seen only a postage-stamp headshot on the back of a book, but thought I recognized him.

“Are you James Salter?”

“Yes.”

That monosyllable was worth recording. Uttered almost as an abrupt sigh.

“I’m a great fan of yours,” I said.

The conversation moved quickly beyond pleasantries (who and what I was: a poet, running an art gallery) to a level of reciprocal energies in both Jim—as he had introduced himself—and Kay, his partner, all underscored by my exuberance in meeting them. They’d driven down to Santa Fe from Aspen and had been in town for a day and a half.

“We’re staying at La Fonda,” Jim said. “Come over and have a drink with us when you finish up here.”

I’d read A Sport and a Pastime when it came out in 1967; then the two earlier novels, The Hunters and The Arm of Flesh—lesser, but with glittering veins of what he was to become—as well as a few brilliant short stories. My wife and I had read Light Years, his most recent book, almost to each other. It was a portrait of a marriage and in a certain way had followed us to Mexico, Santa Barbara, Key West, and, finally, Santa Fe, in the erratic trajectory of our own unraveling lives and eventual separation. It was now 1978—I’d been there for a year.

La Fonda was three blocks from my gallery, at one corner of the plaza. Jim had given me their room number. I crossed the dark lobby with its ancient tiles and climbed the stairs to the third floor.

“What would you like to drink?” Jim said.

“What have you got?”

“Everything.”

He was strikingly handsome. People remarked on his resemblance to Paul Newman. Kay, younger, with light auburn hair, had a fresh, winsome beauty. The thought crossed my mind that it was a little like visiting the Fitzgeralds on the French Riviera. The hotel had been built in the same period. The room was small, with a few obligatory Southwestern features—latillas on the ceiling, a reproduction of a Navajo sand painting on the wall—and cluttered with things they’d brought with them: their “bar,” a pile of books. I was too dazzled to remember much of what was said that evening. We talked at one point about how he wrote—first drafts by hand and later on an IBM Selectric typewriter.

I asked what his handwriting was like. “It’s nothing out of the ordinary,” he said. “There’s a letter I just wrote, over there on the dresser—you can look at it if you like.” It was a full page, written with a fountain pen in clean, even lines without an error, on a sheet of La Fonda stationery. (Over the next three and a half decades, the letters I received from Jim—a number in the hundreds, many of them handwritten—were equally flawless and often on hotel stationery.)

Europe might have been mentioned that night; it came up early in our conversations, along with the fact that I had never been there. “That’s hard to believe,” said Kay. “You’ve got to go!” Jim added, “We’ll take you with us next time.” As if a relived image had intervened in his thought, he said, “Ah, my boy, you’re going to love it!”

By Europe, Jim chiefly meant France. His standard description of Europe was that Italy had a few charms, Austria and Switzerland were places to ski, but other than that, France was it. “What about Spain?” a friend of theirs asked, one night in New York. “I suppose,” he shrugged. “Hemingway liked it.”

They were planning to drive back to Aspen in the morning. I mentioned that if they wanted to spend a few more days in Santa Fe, I could offer them my apartment, explaining that I had a living space in the back of the gallery, where I stayed when guests were in town.

“Let’s take a look at it,” Jim said.

The apartment was an upstairs studio in a compound set back from the street. A hammock hung at one end of the main room on a narrow, glassed-in sun porch. Jim put Kay in the hammock, rocking her back and forth. “How do you like this, my darling?” The question was delivered in a rhetorical tone, like stage dialogue.

***

We saw one another in the evenings over the next few days, and once or twice made dinner in the apartment. Jim’s manner of speaking had an edge of something like artifice, as if it were shaped by print, with some of the same remove and distance. It was unusual enough that I asked about its source. “Practice,” he said. A woman, a documentary filmmaker who had known him in California, once complained to me: He makes you jump through hoops. It was true; he used speech sometimes like a puppeteer’s strings. But it was also style and delivery. Our early conversations in Santa Fe were made up of the rush of mutual involvement. He told stories with great flair; you could sense a repertoire. “Saul Bellow and I bought a house together in Colorado, an investment house,” he said. “We worked on it ourselves. One day we were up on the roof, nailing shingles. Way down in a field, a man rode by on a horse. The horse threw him. He was hollering or something, I guess. Anyway, Saul climbed off the roof and went down there, because he’s interested in things like that.”

We talked mostly about books and writers. Jim was conservative in his references and gave little credence to the achievements of anyone outside the mainstream of literature. He said he wished he’d been at Columbia, with Lionel Trilling, instead of at West Point, and was currently reading Trilling’s book Sincerity and Authenticity. Except for Dubliners, he considered James Joyce batty. He thought the abstract expressionist painters were fraudulent artists who couldn’t draw. He knew nothing about music; he didn’t like jazz. I told him that his own work contradicted these notions and how much he was admired by then-nonestablishment figures, like John Ashbery and Robert Creeley.

He said, “I think I got a letter from him.”

“From Creeley or Ashbery?”

“Yes, one of those guys.”

The divide in poetry between the establishment and the postwar avant-garde was still, in 1978, a tangible conflict. Ashbery had famously written that Elizabeth Bishop was probably an establishment poet and that it was a good thing because it proved that the establishment wasn’t all bad. When I made, in passing, a negative comment about rhyme, Kay, a journalist who wrote for various magazines, seemed affronted.

A picture, not just of limits, but of a kind of circumscribed literary attitude in their lives, began to take shape.

“Your poems rhyme,” she said to Jim, “at least the ones you’ve sent to me.”

His response had the perfunctory tone of being the authority in her life. He acknowledged that most contemporary poetry didn’t rhyme. Then with an edge, he added, “But poetry has always rhymed, and will again.”

I gave them a copy of my translation of L’Après-midi d’un faune, which had just been published, hoping that Jim, whose work had a place of its own in the literature of France, might like it.

“Dust on my head,” he said. “You’re down here translating Mallarmé, and I’m up in Aspen doing I don’t know what—but not that.”

We were walking back through the town after lunch at Tia Sophia’s restaurant. The day was cool, with a sky of pristine blue against the soft edges of adobe buildings.

Kay asked how I’d learned French.

“I didn’t,” I said. “I’m not at all fluent.”

“But,” Jim said, “if you’re not fluent, how can you translate a French poet, especially one like Mallarmé?”

“You work backward from other translations.”

“But you don’t know yourself, firsthand, the exact thing being said.”

“That’s available. You can get the meaning. Making it into a poem, in English, is the hard part.”

He held on to his position, implying that a lack of fluency equaled a form of deceit, as if I were trying to get away with something—or, more bizarrely, as if the goal of my efforts was to make people think I spoke French.

It was an unexpected confrontation. I was shut down, out of a sense of deference. I explained that it was something like Pound’s Sextus Propertius or Cathay.

“Well, I haven’t read them,” he said. This attitude was a permanent component of Jim’s makeup, a militant disdain that surfaced like a reflex. This attitude was, in the scope of a much more complex and generous intelligence, a minor quirk that often had to do with underestimating the depth of something he didn’t know. It belonged to the swagger of self. Fairly late in his life he became friends with Kenneth Koch, who wanted to meet him purely out of admiration. “He’s my favorite prose writer,” Kenneth told me. Of Kenneth’s work, Jim said, “It’s not poetry—it’s just clever writing broken into lines.”

It was disillusioning to encounter these biases and recalcitrant positions in someone I revered. On the other hand, the wholesale dismissal of establishment writers, like Trilling, by a band of loosely connected poets, including me, could easily be seen from Jim’s view as simply foolish. Jim and I plowed through disagreements with the attitude that we could afford them. They brought into sharp focus challenges particular to, and made viable by, the responsibility of a friendship.

Our back-and-forth was agile, sounding out depths and wavelengths. Things were said by both of us to please, to impress, to entertain. He told a story about coming back from Europe on the QE2. Something had gone wrong. All the toilets on the main deck were stopped up. This had gone on for two or three days. Finally, the captain came on the intercom to address the passengers. I interrupted him and supplied the line: “The ship is stinking! The ship is stinking!” Jim’s laughter burst out as if a switch had been thrown. He was wiping away tears by the time he recovered.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “What did the captain say?”

“No, nothing, nothing, yours is better.”

One night, in the apartment, Jim read to Kay and me a section from the manuscript of Solo Faces, which he was working on. It was written first as a film script, commissioned by Robert Redford. When Redford decided not to do the movie, Robert Ginna, editor in chief at Little, Brown and a friend of Jim’s, contracted to publish it as a novel. Hearing it in Santa Fe, at an altitude of seven thousand feet, with mountains rising above the town, was like a palimpsest of real and metaphoric heights resonating with each other.

***

Jim was fifty-two when we met, fourteen years older than I. It was an age gap heightened by profound differences between his life and mine. Growing up, he had lived for a period in the Carlyle Hotel. His father, a retired army colonel, was a businessman in real estate. Jim was an only child. He went to Horace Mann School, where Jack Kerouac had been a couple of years ahead of him. Mildred, his mother, whom I got to know, continued to tell him into his seventies that he was a prince. He gave up an acceptance to Stanford and went to West Point at the request of his father, who had gone there himself, graduating first in his class. After college Jim joined the Air Force and became a fighter pilot in the Korean War, flying more than one hundred missions. With the publication of his first novel, The Hunters, he changed his name from James Horowitz to James Salter. The novel was successful and made into a movie, starring Robert Mitchum. Jim resigned his commission in the Air Force. (It was, he said, the hardest thing he had ever done.) A career of writing films followed. He wrote Downhill Racer for Robert Redford, The Appointment for Sidney Lumet, and Three, starring Charlotte Rampling and Sam Waterston, which he also directed. By the time we met he was the author of four novels.

In comparison, I grew up with a single mother in a small town on Galveston Bay, where I quit school in the ninth grade.

At the end of Solo Faces, the main character, Rand, at age forty or so, is living a kind of white-trash existence in the Florida panhandle, with the purity and anonymous glory of his life as a climber behind him.

He had a small apartment, two rooms and a kitchen, neat and somewhat bare. There was a wooden table with books above it on a shelf, a hammock, a wicker couch. The sun came through the windows in the morning and poured on the empty floor.

It was a description of my apartment in Santa Fe. The novel came out the year after Jim and Kay were there. We’d kept in close touch. Soon they moved to Sagaponack, on the south shore of Long Island. I was in New York for a few days and borrowed a friend’s car to drive out to visit them.

“We’re having flank steak with a Bordelaise sauce and road potatoes,” said Jim. “Have you ever had road potatoes?”

“They fall off the trucks from the farms,” Kay said, “and Jim brings them home.”

“What do you want to drink? I bought you some beer. Or I can make you one of these.” Jim was finishing his second martini when we sat down at the table. I thanked him for the cameo appearance of my apartment in Solo Faces.

“People always recognize their houses,” he said, “but never themselves.”

I asked if I was Rand?

He gave a kind of half shrug.

***

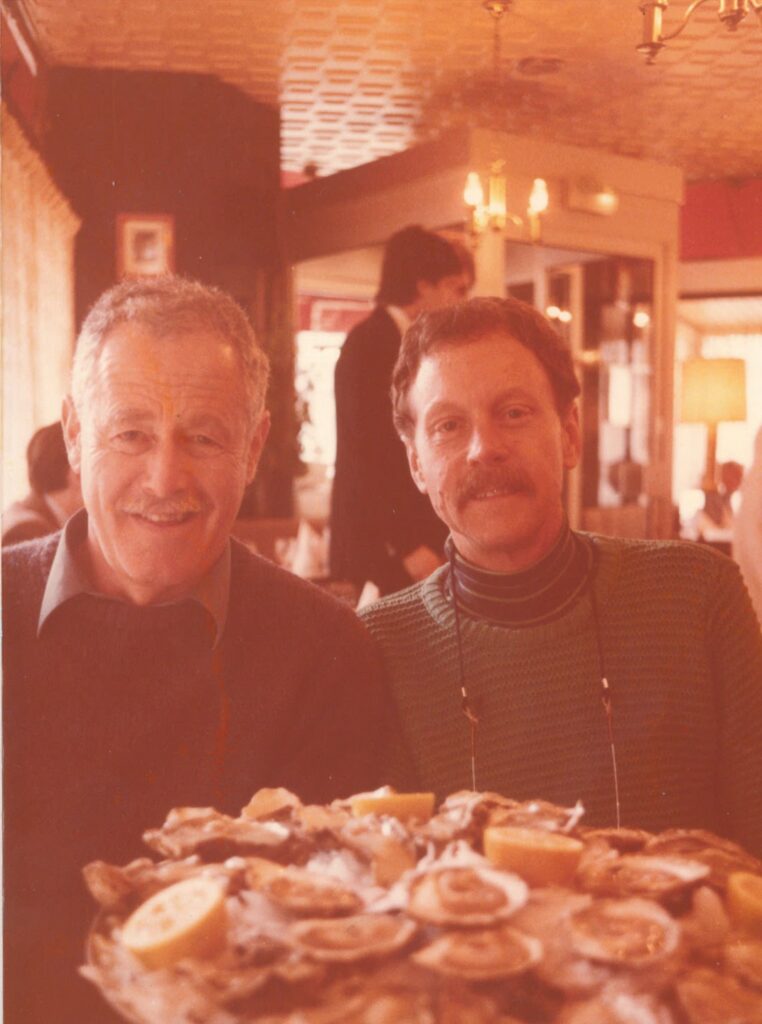

From left, Kay, Jim, and Bill in Sagaponack, 1986. Photograph courtesy of Kay Eldredge.

On that same trip to Sagaponack, Jim gave me the manuscript of a story to read. Over the subsequent years, beginning with the stories that were eventually collected in Dusk, I read almost everything he wrote before it was published. With prose as finely tuned as Jim’s, my task involved little more than taming down his cape work or catching a rare false note. Yet the changes I recommended occurred in calibrations that both tested and deepened our friendship. It went without saying that anything other than absolute honesty would be indefensible. “It stings,” Jim said, “but it doesn’t hurt.”

The gap created by the lack of a father removes from the horizon of a child’s life—to use a figure of Rilke’s—an object, but not a direction, of love. It’s a paradox that hangs on in a kind of midair and becomes to one degree or another an ineradicable part of male friendships. The age difference—in its iteration of fifty-two and thirty-eight, when Jim and I met—had for both of us a father-son element. These positions shifted subtly over time but remained part of the permanent structure of who we were. It was both a challenge and a kind of miracle in my life.

The page was the place we met, not so much as equals but on neutral ground. He paid close attention to the comments and suggestions I made about the work he showed me and would often say, a day or so later, something like, “I put in nearly all your corrections.” It was symbiotic—the desire to please and the parity it achieved in the process. For an ego as redoubtable as Jim’s, the act of listening to whatever I might have to say in these discussions was a clear, almost moral, attention. He was a West Point man, facing with personal honor a situation that tested him. You could sense the control, the strength behind blue, unblinking eyes. Once, in a story that was eventually published in Last Night, I marked the phrase “a mild strabismus,” which he had used in the description of a female character. I pointed out that the phrase came verbatim from my novel Madly.

“Well,” he said, curtly, “you can’t copyright a phrase.”

I reminded him that many people knew we were close. He said he didn’t care if people thought he had taken it from me.

“But they won’t,” I said.

“Oh … they’ll think you took it from me. Okay, I’ll change it.”

In Sagaponack that fall, where I had rented a cottage, life consisted of work, with the salt pond out the front door, the beach and ocean. Aside from weekends with my kids, I was virtually a family member of the Salter household. Jim and I played kick-pass-punt into the last of dusk, or tennis on the local courts. We read the same books. Bobby Van’s bar was the center of Bridgehampton nightlife. There were those girls but not, to quote a poet, “one face.”

Kay was pregnant. Jim sang a variation of a Jerome Kern song, sounding authentically nervous, “And when I tell her / and I’m certainly going to tell her …” This referred to Mildred, his mother. Kay and Jim had talked about the possibility of having a child, and they were ambivalent and at times divided. The subject spilled over as a concern in their small circle of friends because of tensions that were openly aired, but also because it was more complicated than it would have normally seemed. Allan, Jim’s eldest daughter, from his first marriage, had died three years before, in 1980, at twenty-four. It was a horrifying accident. They’d had the guest house in Colorado remodeled by a contractor; a bare wire was touching a water pipe. Allan was electrocuted. They came home from a concert and heard the shower running. It was a tragedy that got folded into silence. At the time it happened, Kay took on the job of informing friends. She called me in Santa Fe. The helplessness that I felt was in some way increased by knowing that Jim, with all his powers, was equally helpless. As he said toward the end of his life, it was something he was never able to write about.

Kay had a miscarriage. However, the work of preparing Mildred, and Jim’s grown children—Nina and the twins, Claude and James—for the possibility of a child was done. Claude and James were all for it; Nina, the eldest, who had never completely accepted Kay as Jim’s partner, was opposed, which everyone was prepared to live with.

Jim’s story “Akhnilo” was published in Grand Street, in 1981. It deals with a sense of the unsayable, the unknowable, the thing that only the center of the night might contain, tangled and beckoning at the edge of the brain’s defeat. It’s unlike any of his other stories. It seems made out of the architectonics of futility—of language breaching its limits, deployed as a narrative shell. I said something along these lines when he first showed it to me, without mentioning Allan. In the same tacitly formed space, Jim said, “You’re reading too much into it.”

***

In 1985, I went to Paris with the Salters. Kay was eight and a half months into a second pregnancy. They had arranged for the baby to be born at the American Hospital, in Neuilly. I’d never been to Europe, and both Jim and Kay saw it as an opportunity to rectify what Jim viewed as a discrepancy in our friendship. They were bringing Sumo, Jim’s corgi, and planned to travel around the continent by car. I could help with the driving and perhaps some of the logistics. A further and more important reason for going was that they had asked me to be the child’s godfather.

We flew out of JFK on a cold late-February night. I bought John Russell’s book Paris to read on the plane. French was being spoken in soft, seductive voices. The cabin was sealed off. America was outside.

Coming into Paris from the airport, the first thing we did was find a bistro open at that hour of the morning that had huîtres. Jim’s enthusiasm was unchecked. “We’ve got to have huîtres! It’s part of your education.” It would have been very hard to talk Jim into eating raw oysters in New York City. But here, served on platters of ice, elevated by a metal stand in the center of the table, they were huîtres and, as Kay said, they were France.

We spent much of the first day in Paris preparing for a road trip. We left the following morning for Klosters. Kay arranged herself in the back seat as comfortably as possible, with Sumo, the corgi, at her side. Kay and I were closer in age, which gave our friendship a solidarity to draw on. Mildred sometimes made veiled remarks that implied we might be more than friends, but that was never true. I was someone Kay confided in. She was factual, fair-minded, and capable of candid affection. Our relationship, coming through Jim, was reaffirmed between us as a value of its own. As we got in the car that morning, she hugged me and said how glad she was that I was in her life—and then added, “And in Paris!”

At Klosters, Jim and I skied with Adam Shaw, the son of Irwin. The Parsenn has the longest ski run in Europe, starting at the top of the Alps, where peak after white peak cluster together like a meeting of the upper reaches of the world. The run itself passes through two small villages on the way down. The act of snaking down the mountain was distilled, by Jim, into slogans that doubled as metaphors for life. Ski the Bumps. All Conditions Are Perfect Conditions.

The next day, we left Klosters on our way to Kitzbühel, to ski the Streif on Hahnenkamm, famous as the most demanding slope on the World Cup circuit. It had been used in Downhill Racer as a prominent part of the film. At Innsbruck, Kay began to have what she thought might be contractions. It was a Sunday. We found a maternity hospital, with a row of women in rockers on a sun porch. There was no doctor on duty. The woman at the desk explained that midwives had the same function as doctors in the hospital, and that Kay could be seen immediately. “That might be better,” Kay said, “than running around on Sunday, trying to find a doctor.”

We waited for her outside. Jim took Sumo for a walk. The day was windless, quiet, with a sallow orange light coming through tall sycamores.

After nearly an hour, Jim said, “I hope she’s not in there having an Austrian.”

As it turned out, Kay’s pains vanished for the next week or so. We returned to Paris. The apartment I’d rented belonged to Dominique Nabokov, a photographer friend of mine in New York. She was the widow of the composer Nicolas Nabokov, Vladimir’s first cousin. Piled under the bed were posters from ballets and boxes of scores. His librettists had included Stephen Spender, Archibald MacLeish, and W. H. Auden. The apartment was in the eleventh arrondissement. Much of the area around the apartment had been left untouched during Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, due to its association with Les Misérables. Jim and Kay’s apartment was in the sixteenth arrondissement. They had rented it through friends. The rooms were spacious and airy, with large windows and modern furnishings. We were each where we belonged.

A couple of weeks later, Jim called in the middle of the night: “The launch is underway. We’re at the hospital, come over as soon as you can.” I got out of bed, dressed, and headed toward the metro, past shops with pulled-down roller-shutters, their colored awnings retracted and gray in the dark. On the corner, the pale green cross of a pharmacy was unlit. A parked moped, resting on its kickstand, stood in front of the doorway. It was cold with low clouds over the city. Already, I felt a sense of propriety about life in Paris and had to remind myself that this—the birth of the baby—was why I was here. The Parmentier metro station was closed. I crossed to the intersection of the avenue and got a taxi.

The baby had been born by the time I arrived at the hospital, a boy, named Theo Shaw Salter. They had opened a bottle of Château Latour 1976, brought for the purpose of moistening the baby’s lips. The obstetrician, who resembled Dr. Gachet in Van Gogh’s portrait, joined in the toast.

Kay looked tired, but thrilled. She held the baby for me to see with a look of triumph. The doctor commended Jim on the wine and talked about playing golf.

Around four or five that morning, after Kay had fallen asleep and the baby was put in the nursery, Jim and I went out to Au Pied de Cochon, ate French onion soup, and drank champagne. I had never seen him as emotionally exposed. He was nearly sixty years old, a man of practiced detachment—joyous.

***

I’d moved back to the city before we went to Europe, taking over a rent-stabilized apartment on Ninety-Third Street that Kay had kept as a workplace in New York. Jim described the location as “a little high,” referring to the numerical values of the streets going north toward Harlem, away from the more fashionable Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties. At some time in the past, Jim had pasted on the inside of the back door, beneath the peephole, the typed phrase “Remember, it’s better than Beirut.” I was working as an independent art dealer and had a new girlfriend, a painter named Mari. We spent a weekend at the Salters’. Mari had read A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years before I met her. The first night we were there, below the surface of amenities, Mari’s presence had an unstated effect. Her looks were part of it. She had almost plain features that came slowly into focus as beautiful, with black straight hair cut above her shoulders. The difference in years that separated my life with women from the settled existence of Jim’s was conspicuous. It was an axiom of his that there was a time for love. When we came down to breakfast the next morning, his first words to me were, “What would you like—a dozen eggs?”

It was a funny line, but it also belonged to a kind of masculine colloquy, like a vestige of military life, where a boyish fascination with sex remains a resonant form both of address and perception. It seems scarcely possible to think of the author of A Sport and a Pastime as being innocent in any way that has to do with women—unless, in fact, you turn the idea around and view the book as the apotheosis of a generational innocence. Jim was in his mid-thirties, an officer in the military, married with children, when he met the girl that Anne-Marie, in the novel, is modeled on. He’d had affairs, but experience isn’t exactly the opposite of innocence. Honor and a sense of duty were strong factors in his life. His father had recently died, after major financial setbacks. Part of what makes A Sport and a Pastime so compelling is its singular intensity as experience. The unnamed narrator of A Sport and a Pastime shadows and finesses the writing. The girl, eighteen in the book, was actually sixteen. It was 1961, the beginning of the decade of the sexual revolution.

After being turned down by almost all the major New York houses, the book was published by George Plimpton as a Paris Review Edition. At the time, they had published only one previous book (Louis Zukofsky’s “A” 1–12). Plimpton’s sole editorial input consisted of a phone conversation. Jim told the story, imitating George’s upper-class accent. “You know, really, most important works of fiction are written in the third person.” Jim said, “What about All Quiet on the Western Front?” adding that he felt his book needed to be in the first person. Plimpton said, “Well, good, in that case, we’ll proceed with it as it is.”

A Sport and a Pastime didn’t sell. It failed to create a buzz. Like a book of poems, it appeared and sank out of sight. Through Robert Ginna, Jim had an assignment to interview Graham Greene for an early issue of People magazine, of which Ginna had been a founding editor, and which in those days published interviews with major literary figures. Jim gave Greene a copy of Light Years, and Greene used his influence to get it published by Bodley Head in England. This not only changed the destiny of Light Years but brought a new and wider readership to A Sport and a Pastime.

When the film about Jim and A Sport and a Pastime was made, in 2011, Ed Howard, one of the producers, wanted to include a scene in which Jim and I would carry on a supposedly spontaneous conversation about the book. We were arranged in the breakfast nook at Jim’s house in Bridgehampton. The big camera on a tripod was inches away. Ed, off camera, was giving us direction, coaxing us along. Jim had retreated. The cameraman, pitching in, asked me if I thought it was necessary to believe in the narrator of the book. I said that it was important because otherwise the book would be read as an act of total narcissism. I might have said more about it, but we were stopping and starting. In the finished film the comment was cut. Yet part of the book’s greatness is that it is a work of unabashed narcissism; the narrator empowers it by being an invention you can see through but at the same time tacitly support. The narrator was in fact a late addition to the book.

***

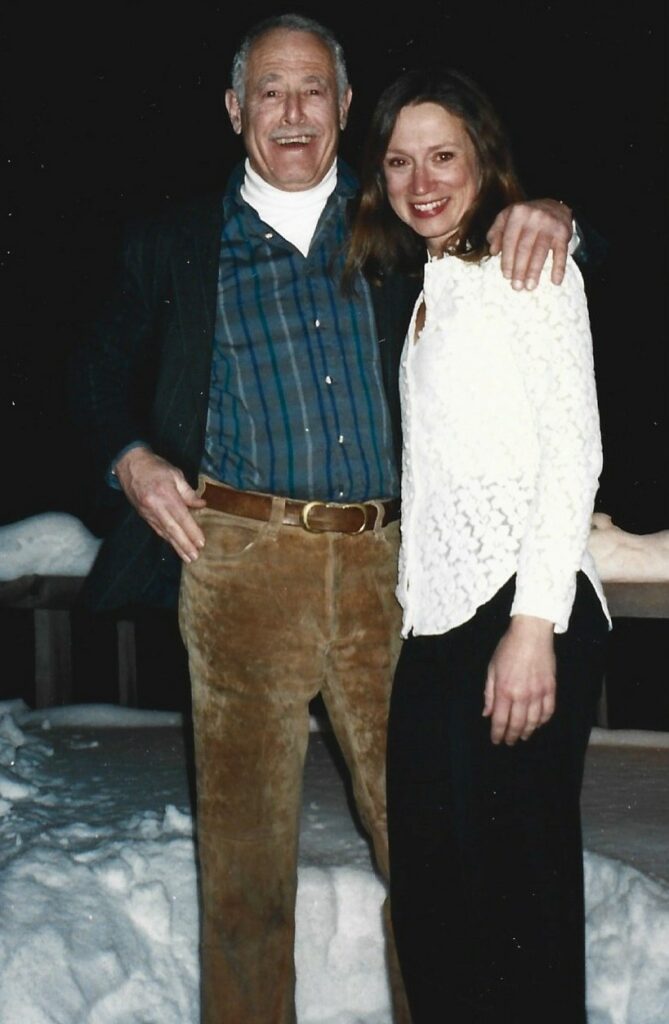

Jim and Kay in Aspen, 1986. Photograph courtesy of Kay Eldredge.

One day Kay and I were talking about a play she’d written. I’d read it and made some comments. We were in the new house they had built, in Bridgehampton. Jim had a desk in the living room, which was cluttered with papers and books, including The Lover, by Marguerite Duras. I remembered a passage in Duras’s book, about writing, that I thought might fit with what we’d been discussing. Jim was doing something in the kitchen, which opened into the living room, and stopped to listen when I read it.

Sometimes I realize that if writing isn’t, all things, all contraries confounded, a quest for vanity and void, it’s nothing. That if it’s not, each time, all things confounded into one through some inexpressible essence, then writing is nothing but advertisement.

Jim was suddenly in a rage, denouncing everything about the quote, trashing Duras, hollering at me. In a fury feeding on itself he kept going, denigrating me for seeing any value in the statement, dismissing Duras as a drunk. It went on. I froze into silence. Kay finally intervened, saying that if he didn’t like the quote that was his business, but it was no reason to behave this way. He calmed down a bit but continued in the same mood. He was sometimes competitive where Kay was concerned but had never been jealous of me that I knew of. Nor did he have any reason to be. Our friendship had involved the three of us from the beginning. This was twenty years later or more. We had been exemplary in our affection for one another. No one had been wounded in what made up the continuing dynamic of our lives. I’d seen Jim lose his temper in other situations, but not to this extent. Eventually he apologized, saying that although he still didn’t like the quote, it didn’t justify the way he’d acted.

A polarity of “vanity and void” in the act of writing amounts to the opposite of fulfilling a set of incremental steps to tell a story; in the same way, “some inexpressible essence” is the opposite of craftsmanship. Duras’s quote—almost the definition of what a poem is—challenges the terms of novel-making in precisely the areas in which Jim most excels. If it hit a nerve, perhaps it was that one. I may be wrong. As Kay said, “He sometimes does this.”

***

Walking with Jim down the streets of Manhattan—or anywhere: Paris, LA—was an experience of male camaraderie. He is at your side, bumping shoulders, a reiteration of bond and forward motion as a unit of being, lead and wingman, in close formation. Few occasions offered him the ease and simplicity of this kind of connection. He imposed, as a matter of course, emotional distance on all the interactions of his life. You understood it as a limitation. He peered in from outside, mildly perplexed at moments of casual intimacy—hugs between friends. It was as if the general qualities he possessed—shyness, reserve, superiority, military authority, manliness, cool—were raised to a pathology. Or perhaps something reductive in the love of women rendered, on a moral scale, other physical expressions of affection false, or misplaced. It’s hard to guess.

Dusk came out in 1988 and won the PEN/Faulkner Award. We went to Washington, D.C., for the ceremony. At the reception for Jim, a gray-haired lady came up to him and said, “I’ve read all your books; you’re as great as Ernest Hemingway.” Jim thanked her politely and shook her hand. When she left, he said, “I resent the comparison.”

I can’t recall the context of the first conversation between us when Hemingway was mentioned. It happened in passing, with Jim repudiating the link between them that could be made, he said, “for obvious reasons.” On another occasion, he spoke with derogation of Hemingway’s “fatuous role-playing.” Once, in Bridgehampton, when Jim and Kay were out of the house, I read two or three chapters of Green Hills of Africa, which was sitting on the coffee table. When they came back, I mentioned how good it was. Jim nodded and said, “Oh, yes—he can do it, no question about it.” Hemingway remained, like a mood or the weather, a presence in his life. Recently, looking at Light Years—my favorite of Jim’s novels—it occurred to me that the opening paragraph could almost be seen as a counterpart to the first paragraph of A Farewell to Arms, which sits like a set piece at the beginning of Hemingway’s book, at once all style and none, an uncanny dazzle down to its final word. In both of the books the opening paragraph is ten lines long; each has a river in it; and each has the formal value of being a prelude to what follows. Whether Jim did this consciously is incidental. The black river without “one cry of white,” is, as an invocation, an appeal in the image of itself to unconscious depths.

***

Jim’s ninetieth birthday party was held at Maria Matthiessen’s house, in Sag Harbor. I have a photograph of him on my wall that Kay took as he arrived. The gravel front yard is in shade, but across the street in the distance behind him, watery sunlight breaks through the trees in a bright grassy splotch of yellow. He has on a white linen suit, carrying the jacket on one arm, with a blue-and-white thin-striped long-sleeve shirt, some papers in one hand, glasses in the other—a wide smile on his face. Tan, moving with youthful agility, he is handsome in a way that defies his age.

Jim at ninety. Photograph courtesy of Kay Eldredge.

The party took place in the backyard, with a few tables set up. It was a gathering of close friends, ten or twelve people. Maria had moved there from Sagaponack after Peter died. The air was warm, moist, with a faint scent of something night blooming. Sag Harbor was a waterfront town, a historic whaling village, on Gardiners Bay. Bob Ginna had lived there for years. We were not far from the Oakland Cemetery, where Jim had bought a plot for himself. Ten years ago, we’d walked through it together. It had an agreeable aspect, with open spaces and beautiful trees. Nelson Algren was buried there. Jim stopped in front of a slender marble gravestone.

He asked me what I thought. Thinner and taller in proportion to some of the other stones, it was Balanchine’s. Beneath the name and dates, it said “Ballet Master.” Jim hadn’t decided yet to be buried here but he knew he didn’t want his body cremated. “I might need it later,” he said.

After dinner a few speeches were made. Bob Ginna’s was especially touching; it overflowed in shifting directions of affection. I said a few words. Kay talked about Jim having been twice her age when they were first together, but that now the difference had dwindled to a smaller percent.

“I’m catching up with him,” she said. At the end of the evening, as people were leaving, Jim came over to me and shook my hand.

“Well, Bill, I don’t know when I’ll see you again.”

It was a statement made in an easy tone but loaded emotionally.

“Don’t be silly. I’ll see you soon.”

Good nights were being said all around. One of the other guests had offered to drive me to the station and was waiting in his car. I was taking the train back to New York. Jim gave me a hug.

I called them nine days later in Bridgehampton. As soon as Kay answered the phone, I knew. She spoke with forced courage in a devastated voice, almost not her own. Jim had died that morning of a heart attack. One of the things that rushed through my mind in that moment, like a wavering in the brain of a child, was the sudden awareness not that he had died, but that he could.

Soon after we first met in Santa Fe, Kay called from Aspen to invite me up for a visit. “We’ve imprinted on you,” she said. “You’re essential to us now.” I felt the privilege it was to be a part of their lives. I was shocked by it, elevated beyond permission.

After a certain point, friendship goes without saying. It exists in its own ordination. When Pound writes “Nothing matters but the quality of the affection,” it’s the word quality that gives the statement consequence. You’re aware that intelligence, discernment, sensitivity, and perception are involved, and that affection of a high level is different from something lesser. The statement is made with the upper limits of quality in mind. Our friendship was like that.

We cherish each other because we die. This was something expressed in various ways over the years. The restraint and distance inherent in Jim’s relation to the people he loved was now an extended measure of what was mourned; not that it should be any different, but that it was there all the time, the hiatus, the not-said, the little death, redolent of a truth, of love bereft of its object. In life, in death. I miss him immensely.

At the birthday party in Sag Harbor, robust and in fine spirits, he stood up in his white suit and made a brief speech about being a writer. “I didn’t have a demon, in the way that some writers do—Lawrence, for instance. I wanted only the praise. That was all.”

William Benton’s poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and other magazines. He is the author of nine books of poetry, including Birds, Marmalade, and Backlit, as well as Madly, a novel. His most recent is Light on Water: New and Selected Poems. He is currently at work on a memoir, of which this is an excerpt.