Blair Hobbs, Birthday Cake For Flannery, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 30 x 24″. Courtesy of the artist.

A painting in Blair Hobbs’s new exhibition features a cut-out drawing of Flannery O’Connor in a pearl choker and purple V-necked dress. She’s flanked by drawings of peacocks and poppies; a birthday cake on metallic gold paper floats above her head. It is titled, like the exhibition, Birthday Cake for Flannery. The number 100 sits atop the frosting, each digit lit with an orange paper flame—marking O’Connor’s hundredth birthday, today, March 25. Glitter and sequins, gold thread and fabric scraps everywhere.

The image is candy to my eyes. I grew up in a stripped-down fundamentalist Protestant church—think Baptist but with a cappella singing. Violence and grace, sin and redemption, idolatry and judgment: When I read O’Connor’s stories for the first time, in high school, I recognized her religious concerns as my own. Fifteen years later I moved to Lookout Mountain, Georgia, where O’Connor’s Southern milieu—backwoods prophets, religious zealots, barely concealed racism and classism—was my literal backyard. I raised chickens in homage to her, then repurposed the coop as my writing studio, where I drafted a collection of stories wrestling with Christianity and sexuality in the American South.

Hobbs, who lives in Mississippi, has been making collage art since she retired from teaching at the University of Mississippi. Her first show, Radiant Matter, was an exploration of the ways her body underwent transformation during treatment for breast cancer. Birthday Cake for Flannery is her second series of collage paintings. Last month I drove from my current home in Chattanooga to Atlanta to see the seventeen paintings in the show. They weren’t installed yet, but Spalding Nix, who owns the gallery, and Jamie Bourgeois, the gallery director, hosted me for a preview.

Jamie unwrapped the paintings one by one. Every canvas—plus one creepy little sculpture wrapped in illuminated wire and encased in a thumbtack-lined shadowbox, meant to evoke the “mummified Jesus” in O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood—is an exuberant explosion of color and found materials illustrating O’Connor’s best-known stories: “Revelation,” “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “The Displaced Person,” “A Temple Of The Holy Ghost,” “Parker’s Back,” and “Good Country People.”

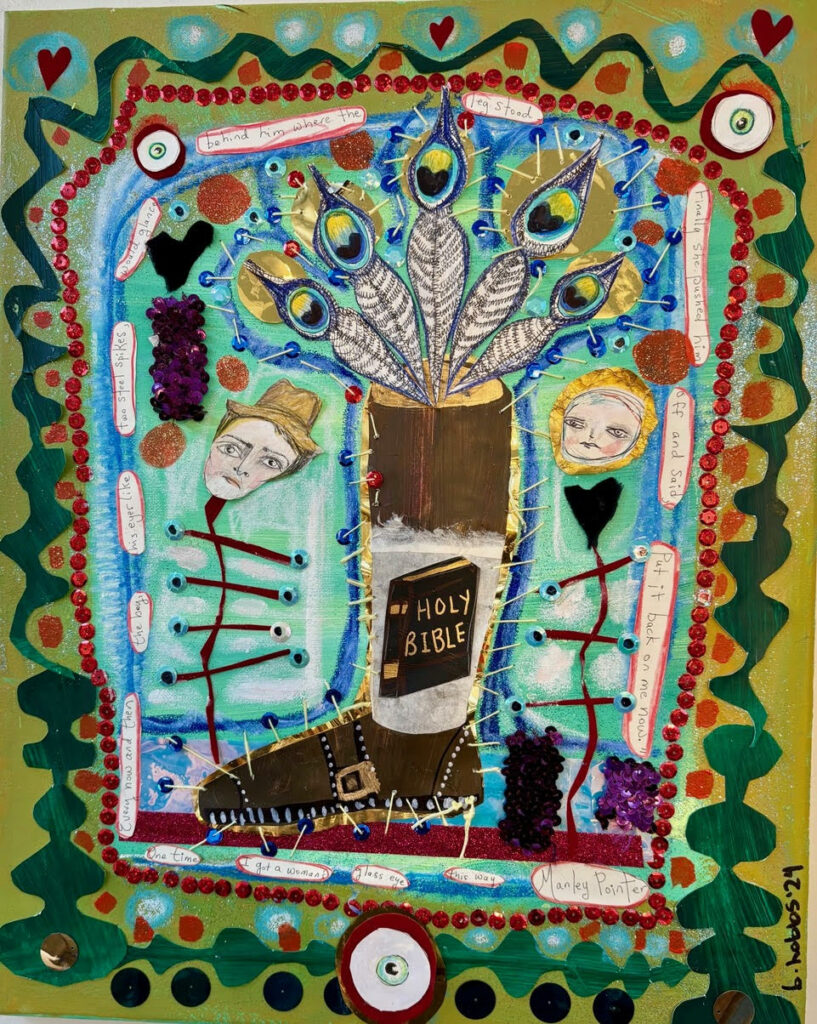

“Give Her Leg Back,” from “Good Country People”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 20 x 16″.

Hobbs draws her characters in graphite and ink and fills them in with paint and colored pencil. She cuts them out and glues or sews them onto painted canvas. And then comes the bling. “O’Connor often writes the sun and sky,” Hobbs writes in her artist statement, “so I wanted the pieces in this show to have an extra dose of shine.” The collages shimmer and sparkle as if backlit: broken Christmas ornaments, rhinestones, bronze dust, gold leaf, metallic tape, silver duct tape. Hobbs also uses embroidery thread, mulberry paper, burlap, tacky plastic placemats, even candy wrappers and paper dolls. Handwritten quotations from O’Connor’s stories and letters are glued onto the final images, a nod to the word art integral to Southern “outsider” artists such as Howard Finster, Nellie Mae Rowe, and William Thomas Thompson.

There is, for the viewer, an I-spy delight of discovery: the better you know O’Connor’s stories, the more you see in each piece. Here’s young O. E. Parker from “Parker’s Back,” who was “heavy and earnest, as ordinary as a loaf of bread.” In Hobbs’s rendering, Parker’s head is an actual loaf of bread wrapped in plastic, with the words Yeasty Boy pasted above him. A second painting shows the adult Parker with Jesus’s face tattooed on his back, stitched through with gold thread and sequins. The letters G, O, and D surround Jesus’s head.

“You’re a Walking Panner Rammer,” from “Parker’s Back”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 40 x 30″.

Two canvases are based on what is arguably O’Connor’s best-known story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” The first depicts the young “cabbage-faced” mother, her head a literal cabbage, thickly veined. Pieces of broken glass, red, surround her body—reminiscent of the family’s car wreck (and the ensuing bloodshed in the woods). A charcoal revolver the size of the mother’s torso is pointed at her head. To her right is her daughter, June Star, a vintage paper doll covered with the words June speaks as the Misfit’s crony leads her into the woods: “I don’t want to hold hands with him, he reminds me of a pig.” In the other “Good Man” painting we see the grandmother’s cat, Pitty Sing; “Bailey Boy” in his yellow shirt with blue parrots; the grandmother in her sailor hat with white violets on the brim; and the monkey in the chinaberry tree. Above these characters is the cut-out title The Misfit. The criminal himself is absent. This omission produces the same vertiginous dread the reader feels on page one. The Misfit is everywhere and nowhere—until he shows up.

My favorite image is from the carnival scene in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” in which an androgynous human with a mustache lifts their dress to reveal the word IT covering the crotch. “It was a man and woman both,” Susan explains to her younger cousin. Above this figure, an open-mouthed rabbit spews forth six babies, evoking the child’s claim to have seen “a rabbit have rabbits.”

Whimsy, humor, glee: these were the words that came to mind, on first viewing. But the glitz and wit are a ruse, belying the deep suffering and darkness beneath the surface.

***

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

I can’t help picturing O’Connor as a toddler growing up “in the shadow of the church,” literally and figuratively, standing in the Koop and peering through a double scrim of screen and windowpanes. When her eyesight failed, she began wearing thick corrective lenses—another layer of remove. And when she contracted the lupus that killed her father, her body itself became a kind of cage. “The wolf, I’m afraid, is inside tearing up the place,” she wrote to her friend Sister Mariella Gable one month before her passing at the age of thirty-nine.

There’s no one like O’Connor for writing the body. With Dickensian specificity (“I have a secret desire to rival Charles Dickens upon the stage,” she confided to a friend) she renders her characters visible, incarnate both physically and metaphorically. For O’Connor, if we are collectively the body of Christ, every human is implicitly the site of both suffering and transformation.

O’Connor also maintained a firm belief in the Eucharist as analogic: a place where the material and immaterial, time and eternity, merged. “If [the Eucharist is] a symbol, to hell with it,” she famously said. A devout reader of Thomas Aquinas, O’Connor would say that this way of seeing was “sacramental”: often in her fiction, signifier and signified become one.

This sacramental vision infuses Hobbs’s work as well. The mother’s face isn’t just cabbage-like, it’s an actual cabbage. Mrs. Turpin in Hobbs’s “Revelation” series isn’t hog-like but a warthog with a human face.

“Look Like I Can’t Get Nothing Down Them Two but Co’Cola & Candy,” from “Revelation”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 30 x 24″.

The body as the locus of suffering and transformation was also the driving idea behind Hobbs’s Radiant Matter exhibition. “I had nineteen radiation treatments for breast cancer,” she writes. “I researched Marie Curie and her discovery of polonium and radium. I’m interested in nature’s repetition, and I saw that radiant ribcages look like fern leaves.” One painting in Radiant Matter features Hobbs as Curie. She’s holding a book where the only legible words are “Even Marie Curie’s cookbooks are under lock and key because of radiation.” A foil halo surrounds her face; the nuclear symbol is emblazoned on her skirt. Her glow-in-the-dark ribs, exposed within her black torso, are iterations of the ferns at her feet.

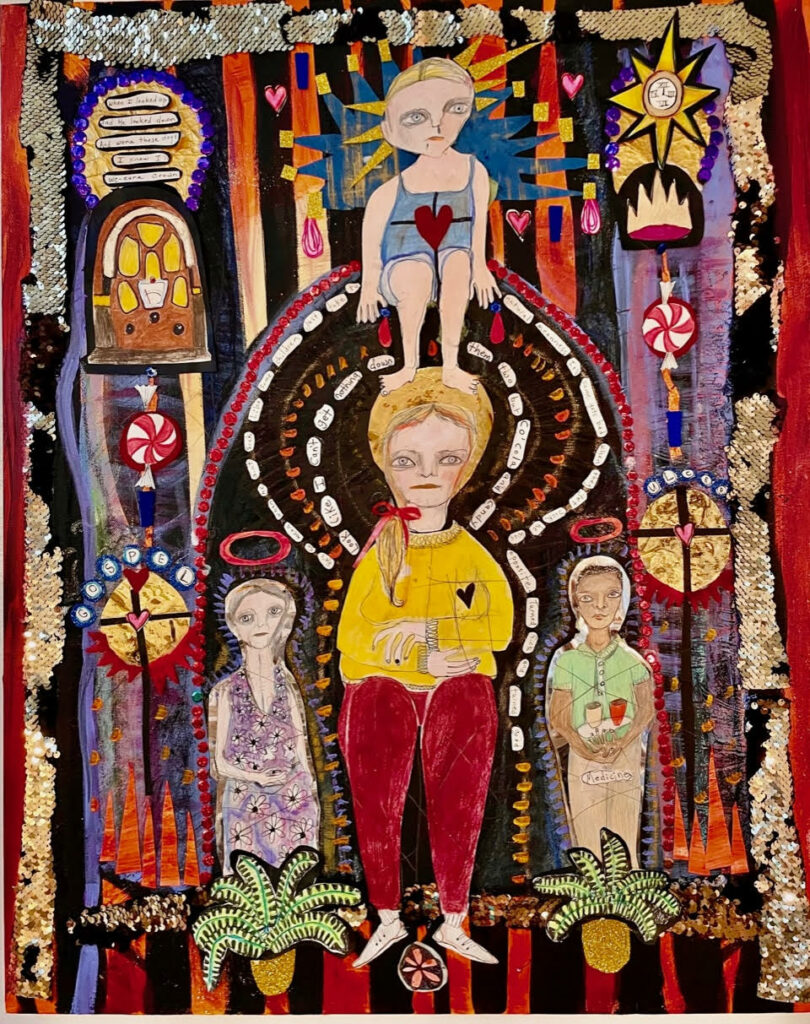

Hobbs, a native Alabamian, was introduced to O’Connor her freshman year at Auburn. She initially tried to fit into the culture, playing the good girl, attending church, and even donning the Minnie Mouse dress her sorority required. “Evangelical hypocrisy was afoot and self-loathing bloomed inside me,” she says. She ended up hospitalized for clinical depression. She began to read O’Connor’s fiction and was moved by “Revelation,” in which Mary Grace flings her human development textbook at the racist (and ableist) Mrs. Turpin. “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog,” Mary Grace says before she’s carted away, presumably to an asylum. For Hobbs, the revelation was in self-recognition. Like Mary Grace, she was seething with rage, but not because she was sick or insane. She was only exhausted by the hypocrisy all around her.

This was 1984, and Hobbs had recently purchased R.E.M.’s second album, Reckoning. The album cover featured one of Howard Finster’s paintings. Hobbs realized that O’Connor’s and Finster’s work were of a piece. Hobbs would go on to study poetry and spend her career teaching creative writing at the University of Mississippi, retiring after receiving the cancer diagnosis—which marked the beginning of her career as a visual artist.

My Revelation: Reading Flannery O’Connor for the First Time, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 16 x 12″.

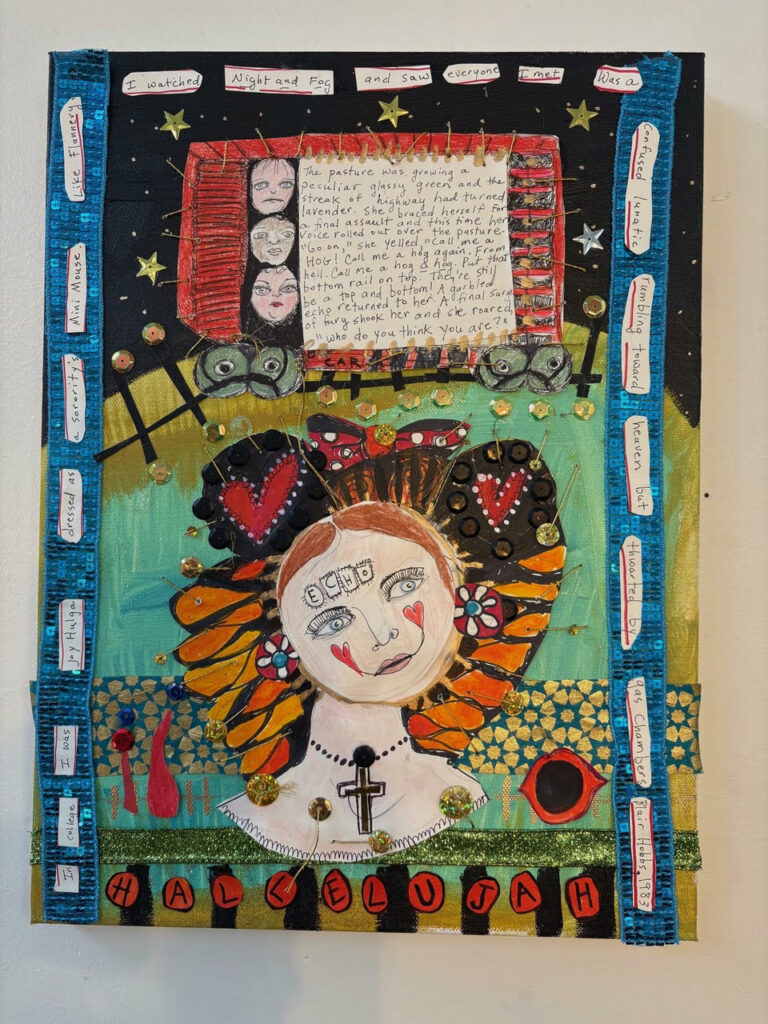

The final piece Jamie Bourgeois unveiled gave me pause. I couldn’t immediately identify its connection to any of O’Connor’s stories. It features the head of a young woman with hearts on her cheeks. The hearts are attached to strings that attempt, unsuccessfully, to tug the corners of the young woman’s mouth into a smile. Monarch butterfly wings emerge from the sides of her face; she wears a crucifix around her neck and a polka-dot Minnie Mouse bow atop her head.

Around the edges of the canvas, in small print, are the only words in the show not written by O’Connor. They are signed and dated: “Blair Hobbs, 1983.”

In college I was Joy Hulga dressed as a sorority’s Mini Mouse. Like Flannery I watched Night and Fog and saw everyone I met was a confused lunatic rumbling toward heaven but thwarted by gas chambers.

Jamie Quatro is the author of Fire Sermon, I Want to Show You More, and Two-Step Devil.