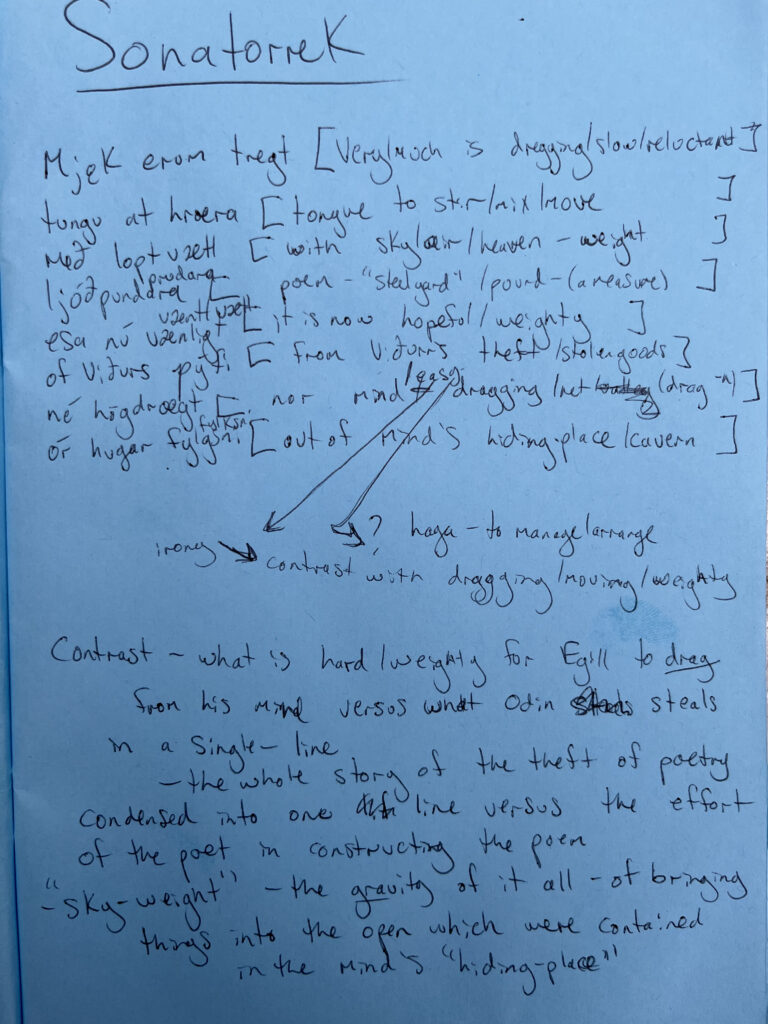

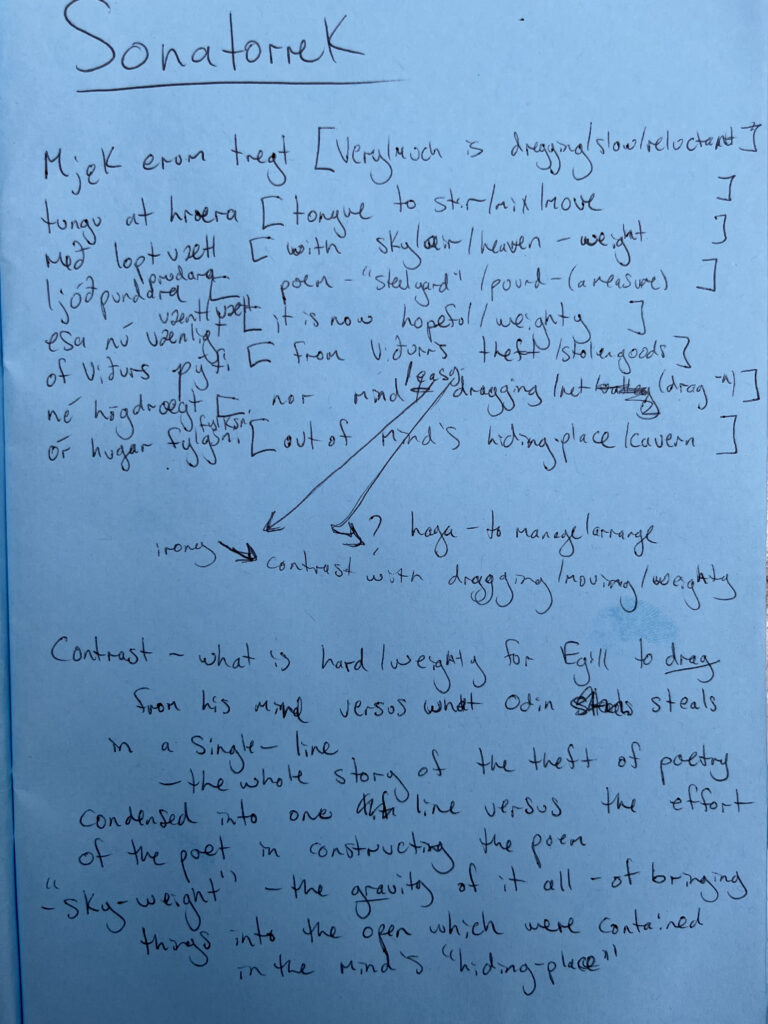

An early draft of a stanza of “Cruel Loss of Sons.”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. A selection from Emily Osborne’s translation of Egill Skallagrímsson’s “Cruel Loss of Sons” appears in our new Winter issue, no. 250.

What was the challenge of this particular translation?

The poetry of the Icelandic and Norwegian skalds, or poets, from the Viking Age—the late eighth to mid-eleventh century C.E.—is notoriously challenging to translate. It was composed orally and passed down orally for generations before being written down in manuscripts. As a result, in the extant manuscripts and runic fragments found on sticks that preserve the poetry, we find variations in redactions, illegible or illogical word choices made by scribes, and frequent references to obscure myths and cultural traditions. Simply understanding a skaldic poem requires a fair amount of background scholarship. The skaldic practice of using compound kennings, in which metaphors and symbols are substituted for regular nouns, adds another layer of complexity. For instance, in this poem, Egill calls his head the “wagon of thought,” his mouth the “word-temple,” and Odin the “maker of bog-malt.”

Above and beyond gleaning the literal meaning of words, a translator must also be able to understand the frequent and surprising tone shifts that add shades of insinuation or emotion. Statements that seem illogical could be ironic or expressing litotes. In “Cruel Loss of Sons,” I found it particularly difficult to interpret Egill’s tone when he speaks of his strained relationship with his patron god, Odin, and the other gods after the death of his sons. In lines such as these, the emotions communicated are ambiguous: “I was on good terms / with the spear-god, / trusted in him, / tokened my loyalty, / until that trainer / of triumphs, champion / of chariots, cut cords / of closeness with me”; and “I’d scuffle with / the sea-god’s girl.” Is the poet indicating betrayal? Sorrow? Defiance? Incredulity? Anger? Self-deprecation? Absurdity? When translating, it can be hard to avoid pinning down the tone too neatly. My task with this poem was to allow grief to carve out its own emotional track.

How did writing the first draft feel to you?

It felt like joining a lineage of transmission fueled by persistence and sorrow. “Cruel Loss of Sons” was, as far as we know, composed orally by Egill in the mid-tenth century. The poem made its way into the later medieval prose saga about Egill, Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, which survives in various forms in various manuscripts and manuscript copies of the thirteenth century and after. Questions of origin and authenticity naturally present themselves. Still, I find this lineage of transmission a compelling testimony to the poem’s ability to move audiences separated by centuries.

Grief, it seems, was the catalyst for transmission. Egils saga Skallagrímssonar tells how Egill was so overcome with grief after his sons’ deaths that he resolved to starve himself to death. His daughter, Thorgerd, convinced him to live by arguing that, if he died too, no one would be left to compose a fitting memorial to their dead kin. She promised her father that, if he composed the memorial poem, she would carve the words on a rune-stick.

Egill opens his poem with an image of struggling to lift up “poem-beams” in order to “drag” poetry out of his mind. The difficulty of constructing an elegy becomes a recurring theme in the work. In the Norse “mead of poetry myth,” an elaborate etiological story referenced in “Cruel Loss of Sons” and other medieval Icelandic sources, Odin gives humans and gods the ability to compose poetry by stealing a fermented, “inspirational” liquid from the supernatural race of the jötnar. I was struck by how Egill mentions Odin’s risky journey to steal this mead so lightly and quickly while spending far more words on his personal difficulties in composing a poem about his dead sons. Composing this poem was grueling for Egill, and I think any translator would feel a sympathetic burden. Translating someone else’s suffering should feel like heavy labor, even across centuries and cultures.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say?

In 2017, I read a freer, more impressionistic translation of part of this poem to an audience at the Vancouver Public Library. It was the first time I had presented one of my Norse translations to a nonacademic audience. The positive feedback and curiosity were overwhelming. Many people were surprised that the Vikings composed poetry at all, let alone sophisticated verse. These reactions first gave me the idea to translate an anthology of skaldic poetry for a general reading audience, partly in order to bring wider attention to a relatively unknown aspect of Viking and medieval Scandinavian culture.

The next time I shared a translation of “Cruel Loss of Sons” with someone wasn’t until 2023, when my husband read my more literal translation of the entire poem. I’m fortunate to be married to a writer, Daniel Cowper—we exchange our writing and are comfortable giving each other’s work tough love. When he read “Cruel Loss of Sons,” he didn’t suggest any edits—a rare thing for him! I have made changes since and am sure I will make more, but I think the positive reactions readers have had to my drafts, though they differ greatly from each other and range from impressionistic to literal, speak to the richness of the original poem. You can tap into various veins and mine precious metals.

When did you know this translation was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

I never think of my translations, or the translations of others, as fully finished products. Nor do I think of a translation as producing a static mirror of an original text. Rather, translating is a bit like setting in motion a disco ball. As the ball turns, it reflects its surroundings in myriad impressions and scatters countless points of light back onto its setting and viewers.

Readers and scholars tend to argue for a “best” translation based on certain criteria—maybe accuracy, beauty, or readability. To me, any translation invites further translation and interpretation. The near-limitless possibilities are exciting, and even readers who have no familiarity with the original text can wonder how things could have been done differently.

What appears of “Cruel Loss of Sons” in issue no. 250 are selections from a longer poem. Srikanth Reddy and the other editors at The Paris Review wisely chose stanzas that track Egill’s intimate response to grief. Other stanzas engage more deeply with religion, myth, war, and social norms. My translation will appear in its entirety in my forthcoming anthology of translations, The Skalds. I imagine that before the book is published, I will make further edits to these stanzas, given that they will appear in the context of the rest of the poem. Rather than considering the version published in The Paris Review to be finished, I think of it as part of a tradition of preservation that can be traced back to Thorgerd and her rune-stick.

Did Thorgerd fulfill her promise, converting her father’s poem from spoken words to written runes? Was she the first preserver and publisher of this poem? Is the story of the poem’s origin even true? I cannot know for sure, but I can say I am inspired by the drive of the Vikings and their descendants to preserve and pass on their stories and poems, no matter the difficulties.

Emily Osborne is the author of the poetry book Safety Razor. Her anthology of translations of Old Norse poetry, The Skalds, will be published by W. W. Norton in 2027.