For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Hua Xi’s poem “Toilet” appears in the new Winter issue of the Review, no. 250.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

While I was writing this poem, I was going back and forth from the U.S. to China to take care of a family member. There was a lot of “going” in my life. I was thinking a lot about things that would be “gone” soon.

I think the word go has a lot of depth. It means to go somewhere and it also means to use the bathroom. People will say “I need to go” to excuse themselves politely in a social setting. There’s a feeling of freedom associated with the term that’s somewhat illusory, since the verb by itself, lacking an object, does not actually “go” anywhere at all.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you were writing?

I used to read a lot on the toilet as a child, so the toilet is very much associated with literature for me. While I was writing, I thought of the first pages of To Live by Yu Hua, which has a scene where a man is trying to shit into a manure vat and his legs are frail and shaking. I’ve actually only ever read the first few pages of the book, but that image stayed with me. Later on, when I was editing “Toilet,” I remembered a passage in an essay by Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, where he talks about the beauty of Japanese toilets. That helped me realize that the peacefulness of a toilet setting must have been experienced by a lot of people over time, not just me, and could be considered a communal feeling. The toilet is a nice place to read because, I think, it mimics the private solace that a book offers; it’s like a personal cubicle where each person can be alone with their own imagination.

I was also writing “Toilet” alongside other poems about different household objects, because I’m working on a manuscript made up entirely of “object poems.” I had to think about how a toilet poem should be different from a table poem or a chair poem, for example, and those differences clarified the poem for me. I decided that a toilet poem should feel a little elegant and clean but at the same time gross.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends? If so, what did they say?

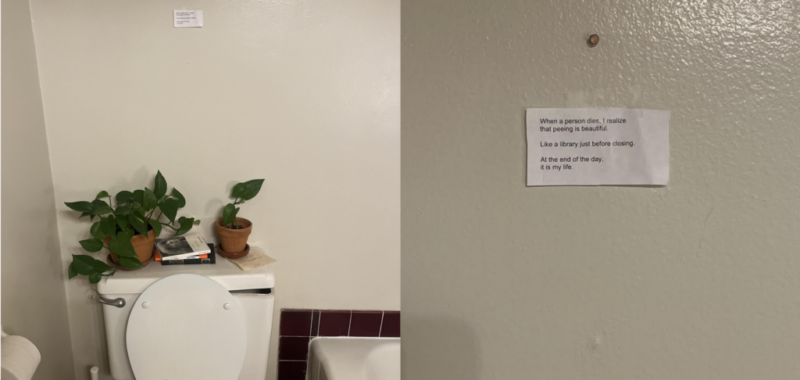

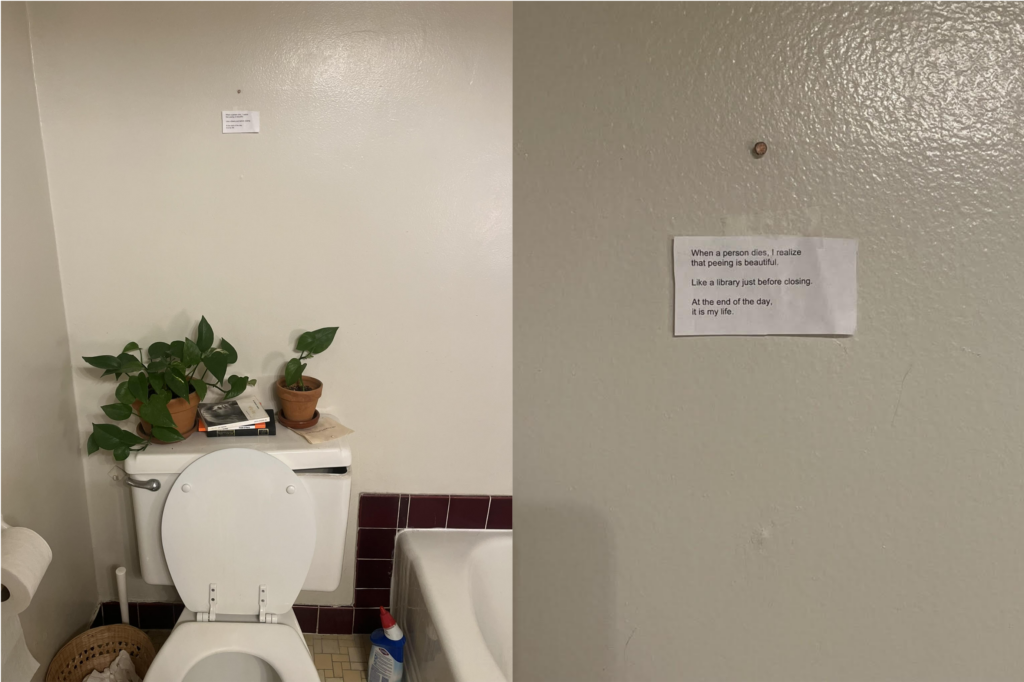

I did. A friend put a Post-it note with the last line of the poem above her toilet, which really made me laugh. I used to tell her to think of me when she peed. Later on, I started texting friends, “Let’s pee together soon” or “Pee well” as a joking way of saying “I miss you.” Another friend of mine put a “Reserved” seat placard on my toilet when she visited my house. That was very important to me as well, and I keep it there. There’s something of those friendships in the poem, which I think gives it its sense of humor.

But this is also a sad poem. There’s a lot of secrecy and privacy in the act of peeing. There’s a sense of shame and of the relationship to the body, which is a carrier of all this familial and historical trauma. I had to find a new relationship to beauty, was what I felt about poetry then. When I’m going through a hard time, there’s sort of a refrain in my head that repeats—something along the lines of, I want to live a beautiful life but I can’t help but notice there is something fundamentally disgusting about it all.

Recently, I started taking photos on 35mm of public bathrooms in both China and the U.S. I think these images eventually feed into my writing. Below are a couple taken in Nanjing. I like how you can see the seasons in them—some of these were taken near the end of summer, so you can still see flowers blooming, or that the sun is really bright outside.

Hua Xi’s poems have appeared in The Nation, The New Republic, and elsewhere. She is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford.