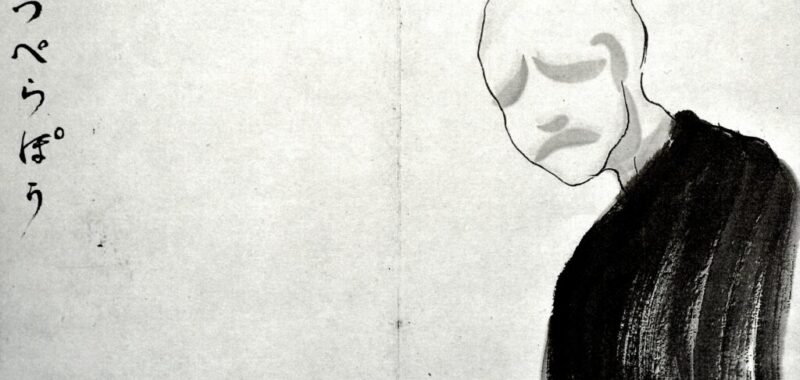

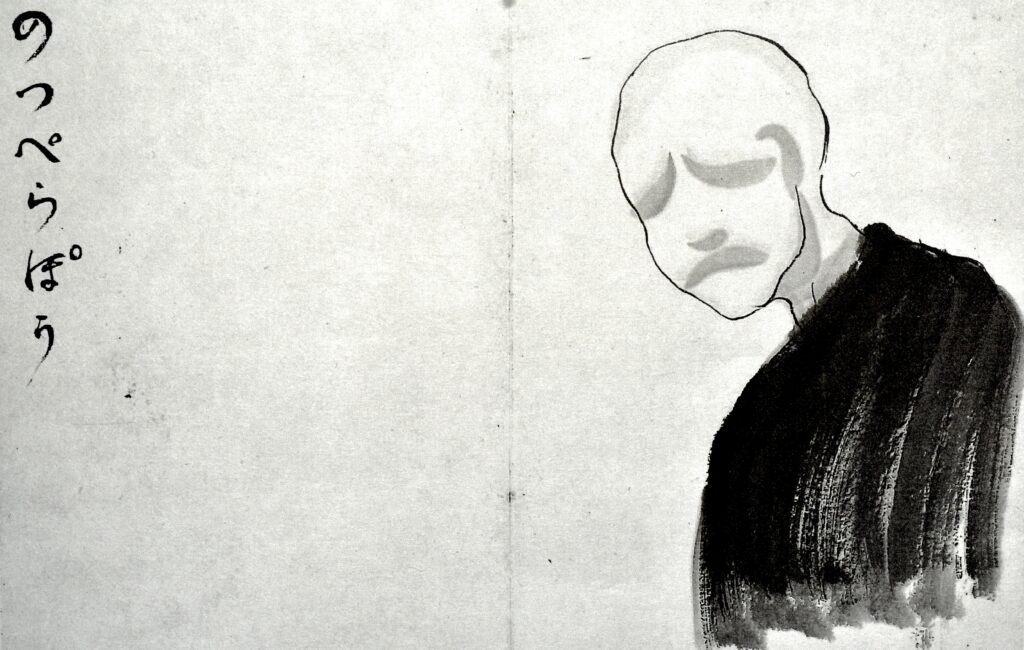

A drawing of the Noppera-bō by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

On the night of July 24, 1927, Ryunosuke Akutagawa swallowed a lethal amount of Veronal, slipped onto a futon beside his wife, and fell asleep reading the Bible. The writer was thirty-five years old. Proclaiming himself an atheist yet preoccupied by Christianity, he had written, shortly before his suicide, “Man of the West,” a series of fifty aphoristic vignettes in which Jesus Christ is an autobiographical writer who has profound insight into all human beings but himself. Akutagawa was a prolific and celebrated writer and one of the first modern Japanese writers to gain popularity in the West. He was drawn to the son of God at a time when he suffered from visual and aural hallucinations, often accompanied by migraines. His wife sometimes found him crouched in his study in Tokyo, clinging to the walls, convinced they were falling in.

Days before he died, Akutagawa wrote a series of letters to his family and friends. At a crowded news conference the day after Akutagawa’s suicide, his friend Masao Kume read aloud a letter addressed to him, “Note to an Old Friend,” commonly referred to as Akutagawa’s suicide note. The letter describes, in dark comedy, the practical banalities that undignify the grandiosity of arranging one’s own death: problems involving the rights to his work and his property value and whether he’d be able to keep his hand from shaking when aiming the pistol to his temple.

It is also a portrait of the author’s interiority in his final moments. “No one has yet written candidly about the mental state of one who is to commit suicide,” the note opens. “In one of his short stories, [Henri de] Régnier depicts a man who commits suicide but does not himself understand for what reason,” he writes. “Those who commit suicide are for the most part as Régnier depicted, unaware of their real motivation.” Like the Christ-poet of his fiction, Akutagawa thought he could see into the souls of all men—except his own. Perhaps he couldn’t look; perhaps he did not want to, for where there is motivation, there is culpability: precisely what he wanted to abdicate in death. “In my case, I am driven by, at the very least, a vague sense of unease,” he writes instead. “I reside in a world of diseased nerves, as translucent as ice.” He mostly wanted rest, he wrote. In “Man of the West,” he writes, “We are but sojourners in this vast and confusing thing called life. Nothing gives us peace except sleep.”

***

Akutagawa was born in 1892 in Tokyo, fourteen years after the city became the new capital of Japan during the Meiji Restoration. His fifth story, “Rashomon,” published when he was twenty-two, heralded a force of emerging talent and went on to enter the canon of modern Japanese literature. Akutagawa wrote critically acclaimed stories, one after another—“The Nose” (1916), “Hell Screen” (1918), and “In the Bamboo Grove” (1921)—many of them still taught in Japanese high schools. Like Manet, who painted his French contemporaries wearing historical costumes in classical poses, Akutagawa often took the characters of historic Japanese legends and reanimated them with a contemporary sensibility. He was viscerally unsentimental. In “O-Gin” (1922), he describes an orphan girl who, along with her adopted Christian parents, will be burned alive unless they renounce God. The girl is the first to renounce her religion, not to save her life but because she knows it is hell where she will reunite with her dead parents. The narrator—Akutagawa always has a narrator, even in close third person—ridicules her as “the single most embarrassing failure.”

Akutagawa’s stories flourished during a time just after the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate, when old customs were falling away to Western influences pouring into a rapidly modernizing country. Modern Japanese literature flourished because there was a robust culture of literary magazines that published criticism, sometimes whole essays devoted to a single short story. The Japanese I-novel tradition—autobiographical novels and short stories that often mixed narration with essayistic lyric—enjoyed high acclaim with the bundan, a coterie of intellectuals, critics, and editors in Tokyo. Like the French, who adored Tokugawa-era literature and art, Japanese publishing did not stake a meaningful difference between autobiographical novels and memoir. The I-novel was said to be inherently Japanese, dating back to the zuihitsu of the medieval Heian period, a genre of autobiographical storytelling braided with lyric essay, verse, and literary criticism.

Much like contemporary autofiction, I-novel fiction often hinged on a confession, particularly unflattering, made by a narrator assumed to represent the author. The bundan praised fiction for how unlikeable its protagonists appeared, which signaled a greater risk by the author—higher stakes. In Toson Shimazaki’s A New Life (1919), the author’s stand-in discloses having sex with his brother’s daughter. Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human (1948) follows a sociopathic misogynist, an outcast of society who is locked up in an insane asylum.

Drawn to the prestige of the I-novel genre at a time when historical fiction was increasingly devalued, Akutagawa began, in what would be his late style, to experiment with autobiographical short stories and personal essays. Throughout these works, we encounter a young man who is funny and self-possessed, erudite in a comic way, uncommonly wise, and susceptible to lust and ambition. In “The Life of a Stupid Man” (1927), the narrator feels a “pain close to joy” after hearing that his mentor, the legendary Meiji novelist Soseki Natsume, has died. Regarding a cast-iron sake bottle with finely incised lines, he has an epiphany of “the beauty of ‘form.’” By listening to The Magic Flute alone, he knows that Mozart was a man who, like him, had “broken the Ten Commandments and suffered.”

Akutagawa’s suicide note is preoccupied with sin and transgression. The writer was “aware of all of his faults and weak points, every single one.” He apologizes vaguely, “I just feel sorry for anyone unfortunate enough to have had a bad husband, a bad son, a bad father like me.” From some of his autobiographical stories, published posthumously, we know that Akutagawa had an affair with the poet Shigeko Hide. He believed the affair, as he disclosed in a letter to Ryuichi Oana, his frequent cover designer, led to his suicide. In “Stupid Man,” Shigeko is pseudonymized merely as “crazy girl” and characterized as a charismatic and vicious woman. “I have not tried—consciously, at least—to vindicate myself,” he writes in a separate note to his friend Kume Masao. “Yet, strangely, I have no regrets.” What comes off the page is guilt only for his lack of guilt. One gets the sense of Akutagawa speaking out of both sides of his mouth, of someone both resisting and desiring to confess, to issue a mea culpa on his own terms.

But from what, exactly, does Akutagawa wish—or not wish—to vindicate himself? Centuries of classic Japanese literature, from The Pillow Book (1002) to The Life of an Amorous Man (1862), had already normalized the practice of adultery. A greater sin might be found in the final lines of “The Baby’s Sickness” (1923), in which Akutagawa recounts his infant son’s near-death illness. Akutagawa admits that he had once thought about writing a sketch about his child’s hospital stay but “decided against it because of a superstitious feeling that if I let my guard down and wrote such a piece, he might have a relapse. Now, though, he is sleeping in the garden hammock. Having been asked to write a story, I thought I would have a go at this. The reader might wish I had done otherwise.”

Akutagawa’s transgression is the act of writing itself, writing that takes suffering as its subject. Akutagawa allegorizes the sadomasochistic desire to tell stories about pain in his masterpiece “Hell Screen.” It tells the story of a Heian painter who can paint only from life. To paint a scene of people burned alive, the emperor arranges to have someone burned in front of the artist’s eyes. The painter agrees, but it is only during the burning when the emperor, smiling, shocks the painter by sending the artist’s own daughter, bound to a carriage, burning in flames. He watches in horror, then radiance—“the radiance of religious ecstasy.” His finished painting, the hell screen, is lauded by critics. The artist hangs himself.

The painter reaches his breaking point at the moment when he confuses his life’s realities with art’s imaginaries. This is a common theme in Akutagawa’s I-novel writing. In the posthumously published “Spinning Gears” (1927), the narrator, Mr. A., becomes convinced that pages from The Brothers Karamazov have been stitched into the middle of a copy of Crime and Punishment—presumably a hallucination. In his field of vision, he begins to see semitransparent wheels, spinning and multiplying, like the eyes or wings of the angel in the book of Ezekiel. “I opened my eyes, and shut them once again once I had confirmed that no such image existed on the ceiling,” he writes.

Born to a “lunatic” mother, Akutagawa was afraid in the years before his death that he, too, would lose the ability to tell what was real and what was not. Perhaps all autobiographical writers experience the moment when the imagination of their recorded memories begins to overwrite what actually happened. Akutagawa’s story “Daidoji Shinsuke: The Early Years” (1924), told in the third person, includes the memorable line: “He did not observe people on the street to learn about life but rather sought to learn about life in books in order to observe people on the streets.” In the beginning was the word. Here was a writer who could no longer distinguish between reality and the confabulations of his own mind.

***

For Aristotle, the tragic hero’s heroism carries the seeds of its own destruction: the tragic flaw. The tragic hero of Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872) possesses no flaw at all, only an inhuman, semidivine surplus that requires him “to do penance by suffering eternally.” Nietzsche’s influence on Akutagawa, of which the latter wrote often, is particularly legible at the end of his life. In “Man of the West,” there are, in addition to Christ, many other “christs,” incarnated in writers like Goethe and Walt Whitman. For their poetic temperament, these poets must suffer, like Christ, a “darkest, most desolate hour,” for “sentimentalism is easily confused with the divine.” In his suicide letter, Akutagawa writes: “I have seen, loved, and understood more than others. This alone grants me some measure of solace in the midst of insurmountable sorrows.” It is his godlike ability to see, love, understand more than others that constitutes his mortal transgression. The postscript to the letter reads: “Reading the life of Empedocles, I realized what an ancient desire it is to make oneself a god.”

By the end of his life, Akutagawa was no longer the artist watching his daughter burned alive; he was in the burning. In “Spinning Gears,” Mr. A. leaves the Imperial Hotel, where he writes, to walk in endless circles around Tokyo, over and over, like Dante’s damned. “I had sensed the inferno I had fallen into.” Only a writer as conflicted as Akutagawa—struggling between sensitivity and indifference, intellectual distance and delusions of the grandeur of his own pain—could effectively sensationalize his own mental illness as it was happening. Akutagawa’s craft was unparalleled in his generation. Here was a young man whose talent had accelerated beyond his own ability to comprehend it, much less control it.

A disordered mind: this affliction that so often appears in stories has, since antiquity, been sent by the gods. (At least as early as “The Bacchae,” of 405 B.C., Dionysus casts a vengeful spell of madness upon the entire city of Thebes.) “I was in hell for my sins,” Akutagawa writes. “I could not suppress the prayer that rose to my lips: ‘Oh, Lord, I beg thy punishment. Withhold thy wrath from me, for I may soon perish.’” In the world of literature, Akutagawa “discovered his own soul, which made no distinction between good and evil,” as he wrote in “Daidoji Shinsuke.” “I have no conscience at all,” he writes in “Spinning Gears.” To him, writing is amoral, has no compass except for the aesthetic, which is its transgression.

***

Each time I read “Note to an Old Friend,” I see a different person. I see a man convincing himself he is a god, or a god convincing himself he is human. I see someone who suffered a pain beyond empathy, immune to empathy. He fantasized about suicide the way people watch TV. A sensitive man distracted by his gifts of wisdom, he resisted the compassion of others because he had no compassion for himself. He numbed his fear with intellect, mistook self-pity for humility. He wanted to be forgiven—but never to apologize. He believed his own self-mythology was a public service.

His only happiness was in the mundane details of everyday life. Yasunari Kawabata, the first Japanese writer to win the Nobel Prize, quoted, in his 1968 Nobel Lecture, a passage at the end of Akutagawa’s suicide letter:

If we can submit ourselves to that eternal slumber, we can doubtlessly win ourselves peace, if not perhaps happiness, but I had doubts as to when I would be brave enough to take my own life. In this state, nature has only become more beautiful than ever to me. You love the beauty of nature, and would no doubt scoff at my contradictions. But nature is beautiful precisely because it falls upon the eyes that will not appreciate it for much longer.

Here, we find an articulation of the Japanese notion of mono no aware, the perception of beauty precisely at the revelation of its transience. Having decided to end his existence, Akutagawa begins to see clearly the beauty of every prior moment in his life, just before its extinction. The things of this world are revealed as beautiful because beauty is but a mask, however thin, for the void that constitutes its meaning. Is this why he didn’t trust the beauty that became visible only after his decision to kill himself?

Akutagawa might have felt a tremor of the spirit that he believed could be pacified only by merging with the void. There’s nothing all too special about that. Sometimes, you can see the void behind the snow falling on the river from the window of a subway car crossing the Williamsburg Bridge. You either make peace with it or you don’t. You can acknowledge the void, clutch your heart, squeeze your eyes closed, say your gratitude list, and then go on with your commute. Most of us know how to do this. We do it every day.

Geoffrey Mak is a queer Chinese American writer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, the Guardian, and Artforum, among other publications. He is cofounder of the reading and performance series Writing on Raving.