At 84 years old, Evelyn Paternostro spends her days working part time as a cashier at Dollar Tree. For decades, she dedicated her life to education, serving as a teacher and principal in Louisiana. But despite years of her public service, she now struggles to make ends meet.

“People at the store ask me all the time, ‘Are you doing this for fun? Why aren’t you retired?'” she said. “Because I need to eat.”

After her husband died, Paternostro discovered she couldn’t collect his Social Security benefits due to a pair of federal policies called the Windfall Elimination Provision and the Government Pension Offset.

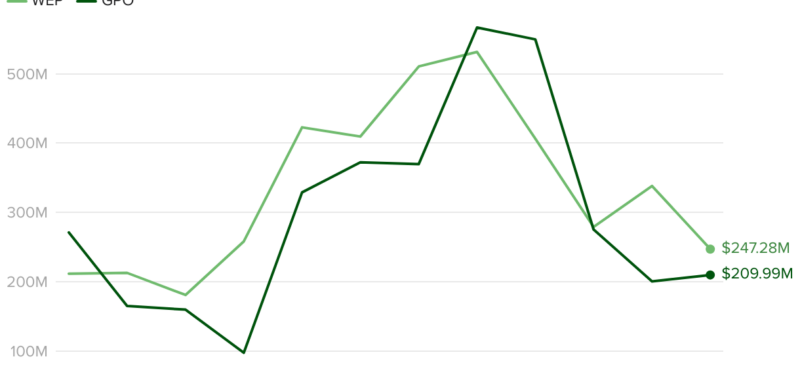

These provisions reduce or eliminate Social Security benefits for millions of Americans if they receive a public pension that didn’t withhold Social Security tax. Retired teachers, firefighters and other public servants are some of the most impacted.

“I was really blindsided,” she said. “I knew I was going to have a teacher’s retirement. I was going to be part of the Louisiana Teachers Retirement System. And I never really thought about my husband’s income and what that would mean to me.”

Kati Weis / CBS News

Who is affected?

Nearly 2.8 million individuals across the United States are impacted by WEP and GPO. Its effects extend to all employees of state, county, municipal and special districts in 26 states. Teachers in 13 of those states, including specific districts in Kentucky and Georgia, also feel its impact.

In Massachusetts and certain districts in Rhode Island, not all municipal employees, but only teachers are impacted.

The purpose of these two 1980s-era programs was “so that there was no way you could ‘double dip’ into both a federal pension and Social Security,” explains Jill Schlesinger, CBS News business analyst.

The Windfall Elimination Provision affects people who qualify for Social Security benefits through their job but also receive a pension from another job where they didn’t pay into Social Security.

It may decrease their Social Security payments by up to half the value of their pension.

For example, Michelle Cosgrove’s benefits were cut in half, reduced from $866 a month.

Cosgrove spent the first half of her career as a paralegal, contributing to Social Security, before staying home to raise her children.

Later, she became a public school teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area, paying into CalSTRS, California’s educator pension fund. However, her plans for retirement took an unexpected turn when she discovered the intricacies of the pension system.

When she retired, Cosgrove’s reduced payments affected her ability to pay bills and cover expenses.

The other program, the Government Pension Offset, further impacted Cosgrove after her husband, Mike, passed away in 2022. Despite working in the private sector for decades and contributing to Social Security, his benefits were largely inaccessible to her due to the GPO. Mike, a welding supervisor, was diagnosed with a rare cancer at 52 but continued working until his health worsened. He died at the age of 63.

If pension recipients are a widow or widower of someone who received Social Security benefits, that pension recipient may have reduced survivors benefits or may not receive benefits at all.

If I’d have stayed home and done nothing, I’d have gotten all the money,” Cosgrove said. Had I known this, I might not have gone into teaching. I’d have picked something different.”

The GPO mainly affects women, with 83% of those impacted by GPO being female, according data from the Congressional Research Service.

“When you see the numbers of the GPO elevated, it’s because many of those people were probably teachers and married to somebody who worked in a Social Security job,” said Joslyn DeLancey, vice president of the Connecticut Education Association. “They’re not going to get that spousal Social Security. … It’s such a messy and nuanced thing.”

Paternostro estimates she would have received $2,500 a month in Social Security benefits — about $300,000 over the last decade.

“That’s a lot of money,” she said. “That’s more money than I can imagine.”

But these policies brought a different kind of heartache for Dede Ruel, a retired school psychologist in Illinois.

She said she recently received a letter from Social Security informing her that she owed more than $13,000, reducing her Social Security checks by 21%.

According to a CBS News analysis of federal data, these policies are one of the most common reasons for Social Security overpayments, which have totaled more than $450 million in fiscal years 2017-2021.

“I have been trying to appeal it through their process and I’ve been denied at every level,” Ruel said.

Bipartisan support for the Social Security Fairness Act

The Social Security Fairness Act, one of the most bipartisan bills in Congress this session, aims to repeal WEP and GPO.

The House voted to pass the legislation Nov. 12. The Senate is expected to vote on the Social Security Fairness Act this week.

Social Security is projected to run out of funds in 2035 unless there is a change made to the fund’s cost and revenue system.

Even though supporters of the Social Security Fairness Act argue it will only drain the Social Security fund six months earlier than otherwise expected, some critics believe there are better solutions, suggesting states should restructure their retirement systems to address the root causes rather than rely on federal fixes.

“A lot of the critics say this is gonna cost a lot of money, almost $200 billion dollars over the next 10 years,” explains Schlesinger. “Critics say there is a reason why we force people to pay into the Social Security system. These are two separate systems. If we need to fix Social Security, let’s fix it. Let’s not just do a repeal which is essentially a Band-Aid.”

Rep. Garret Graves, a Republican from Louisiana who spearheaded the bill, said, “People should receive benefits based on what they paid into the system. That’s what the formula should largely be based upon. I understand the efforts back in the ’70s and ’80s, but the overcorrection has likely taken $600 to $700 billion in benefits from these folks.”

Devin Carroll, a financial planner, encounters many clients who are “completely taken by surprise.” Carroll often instructs his clients to use the Social Security Administration’s WEP calculator, a tool that calculates benefits with the impact of the WEP factored in.

Carroll explains that it can be challenging to figure out future Social Security benefits. The benefits formula includes “bend points,” which are adjusted annually based on wage inflation.

These adjustments are crucial because the actual amount of the WEP reduction is determined the year a person turns 62.

“You have to make some projections, some assumptions about forward-looking inflation, both price inflation and wage inflation,” Carroll explained. “Once you do, then you can start to work through that and use a calculator like the SSA has that will do a lot of that for you, and it will tell you what your WEP adjusted for retirement age benefit should be.”

Carroll also gets to see the impacts of these provisions firsthand. His daughter-in-law is a teacher in Texas and his son is a firefighter in Texas.

“In essence, this money has been stolen from all of us for all these years,” Paternostro said. “It’s not fair.”

Jill Schlesinger

contributed to this report.